The Values Pyramid

A Clarity Framework for defining and aligning organizational values.

The Power of Values That Work

Some organisations have cracked the code. Their values do not just inspire — they direct behaviour and decision-making at every level. Walk into these companies and you can feel it. People know what matters. They know what to do when the answer is not obvious. They do not need to escalate every hard call because they already know what the organisation would choose.

Apple embodies innovation and product excellence. Every decision, from product design to customer service, reflects this unwavering focus. Employees and customers alike understand that while Apple products come at a premium, the quality justifies it. Engineers have permission to delay a release until it is right. Designers have permission to say no to features that compromise elegance. This clarity does not just simplify decisions, it makes the entire company mission-focused. People want to work at Apple because they want to build things they are proud of, surrounded by others who feel the same way.

Amazon has leadership principles that leave nothing to interpretation: customer obsession comes first, hard work is non-negotiable and frugality is a virtue. Employees who resonate with these principles are drawn to the company, knowing exactly what will be expected of them. No one questions a team prioritising customer happiness over short-term cost-saving measures. The alignment between values and action is seamless. Amazon is not for everyone, but for those who thrive on intensity and impact, there is nowhere better.

Netflix took perhaps the boldest path: "We're not a family, we're a sports team." This is not corporate evil, it is a commitment to excellence. Netflix believes that talented people do their best work when surrounded by other talented people. The bar is high. The expectations are clear. If someone no longer fits the evolving needs of the team - even a loyal contributor - they may be let go, with gratitude for their past service. In return, employees get to work alongside exceptional colleagues on problems that matter, with the autonomy to do their best work. For people who want to be challenged and who refuse to coast, Netflix is magnetic.

What sets these organisations apart is not that they have values. Everyone has values. What sets them apart is that their values guide how decisions are made, from top to bottom. The values are not decorations. They are operating instructions.

These are also companies people want to be a part of. They attract talent not just with compensation but with clarity, the promise that you will know what matters, that your work will be evaluated fairly against known standards and that you will be surrounded by people who share your commitment. That is rare. Most companies cannot make this promise because their values do not actually mean anything.

But yours could.

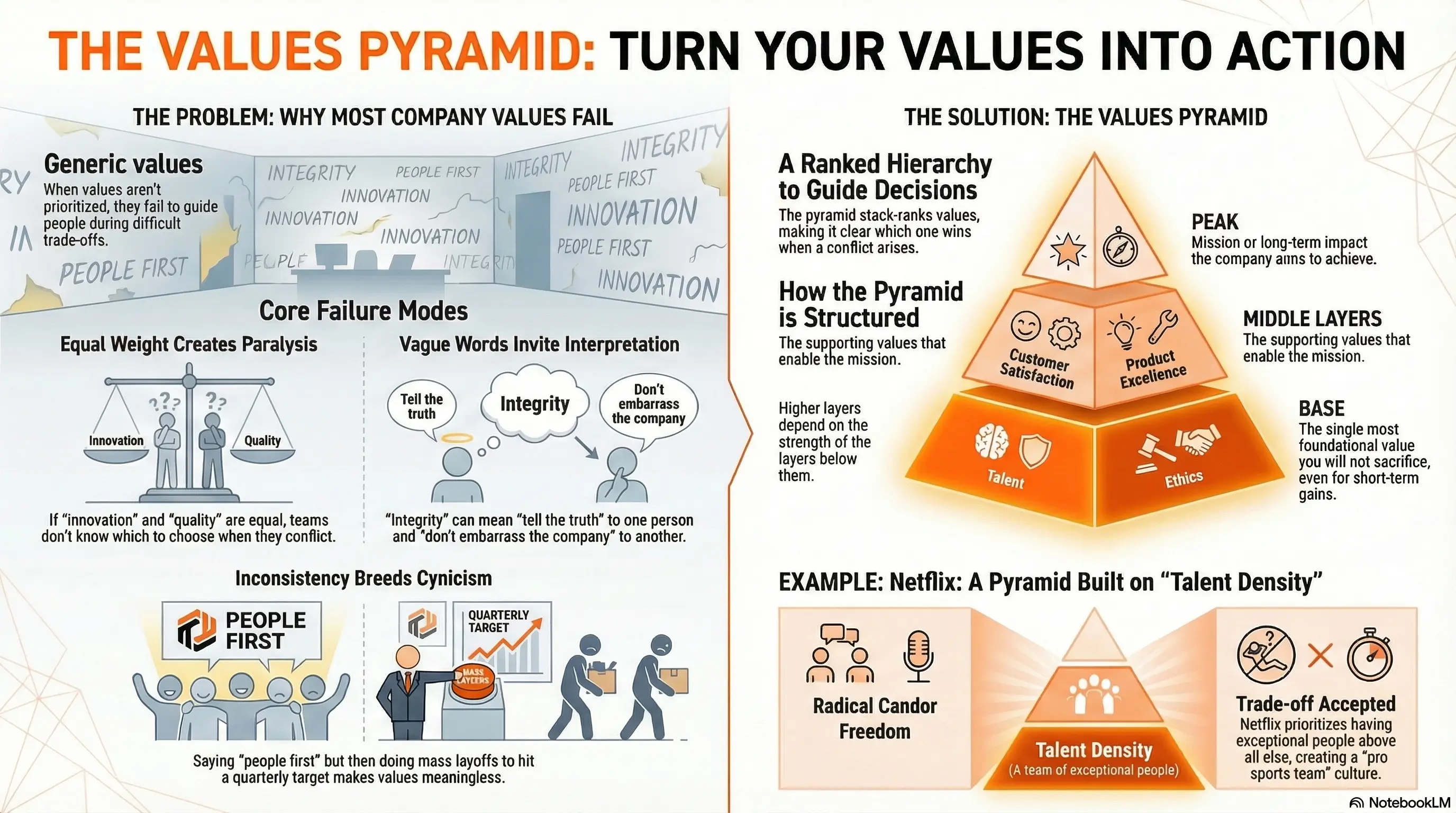

Why Most Values Fail

Now walk into most organisations and ask a random employee: "What are the company values?" They might remember three out of five. They might remember none. Even if they do remember all of them, ask the harder question: "How do these values help you make decisions when you are stuck?"

Silence.

Most companies have values that sound good but do not do anything. Integrity. Innovation. Customer obsession. Teamwork. It is hard to argue against any of these — which is precisely the problem. When everything sounds important and nothing is prioritised, values become wallpaper. They decorate the culture without shaping it.

The gap between companies like Netflix, Amazon and the typical organisation is not that they chose better words. It is that their values resolve conflict. They tell people what to trade off against what. They make hard decisions easier because the organisation has already done the hard thinking.

How values fail in practice:

-

Equal weight creates paralysis. If the company values both innovation and customer satisfaction, which wins when a new feature is delayed to ensure quality? If the answer is not clear, people guess — or escalate to someone who will guess on their behalf.

-

Vague values invite interpretation. "Integrity" means different things to different people. One person reads it as "tell the truth even when it hurts." Another reads it as "do not embarrass the company." Without specificity, people optimise for their own interpretation.

-

Values without hierarchy become politics. When leaders disagree about priorities, the dispute is resolved by whoever has more power, not by a shared framework. The organisation learns that values are negotiable, which means they are not really values.

-

Inconsistency breeds cynicism. When the company says "people first" but fires half the workforce to hit a quarterly target, employees notice. When innovation is celebrated in town halls but punished when it causes delays, employees stop innovating. Values that are not lived become evidence that leadership cannot be trusted.

The problem is not that these organisations lack values. The problem is that their values are not prioritised. When everything matters equally, nothing guides decisions. When values are just a list, employees are left scratching their heads, unsure how to apply them when tough choices arise.

The fix is not better words. It is a structure that makes values actionable.

Purpose

The Values Pyramid is a model for turning values into decision-making infrastructure. It puts values front and center and answers the question that most organisations avoid: When our values conflict, which one wins?

It is, in essence, a strategy that articulates how you believe your culture will contribute to your success.

The pyramid takes your values and stack-ranks them into a hierarchy where each layer supports the one above it. The foundation represents what you will not sacrifice, even for short-term gains. Each ascending layer depends on the one below.

This is how Netflix can let go of talented people who no longer fit. This is how Amazon teams know to prioritise customer satisfaction without checking with leadership. This is how Apple maintains its focus on product excellence even when the market demands faster, cheaper alternatives.

These companies have, whether explicitly or implicitly, built a values hierarchy. They know what comes first. And because they know, so does everyone else.

The Pyramid

The Values Pyramid is a visual hierarchy where each layer supports the next. Like Maslow's hierarchy of needs, if the foundation crumbles, everything above it is at risk.

The structure:

At the base is your most foundational value, the one you would not sacrifice even under pressure. This might be your people, your product integrity or your ethical commitments. It is the thing that, if compromised, would hollow out everything else.

Each ascending layer represents a value that depends on the one below. You cannot sustainably deliver excellent products if your people are burned out and disengaged. You cannot sustainably delight customers if your product is mediocre. You cannot sustainably generate profit if your customers are unhappy.

At the peak is your mission or long-term impact — the aspirational outcome that all the lower layers exist to enable.

Why a pyramid?

The pyramid metaphor does real work. It communicates three things:

-

Dependency. Higher layers depend on lower layers. You cannot skip levels. An organisation that chases financial returns while neglecting product quality is building on sand.

-

Priority. When values conflict, lower layers take precedence. This is not about importance — mission may be the most inspiring value — but about sustainability. You cannot achieve long-term mission impact if you sacrifice the foundations that make it possible.

-

Stability. The pyramid is meant to be stable over time. It is not a flavour-of-the-quarter exercise. When priorities shift, the pyramid can be updated, but the changes are visible and deliberate — not hidden or ad hoc.

An Example Pyramid

Consider a software company that has defined its Values Pyramid as follows:

Layer 1: Engaged and Talented Workforce (Foundation)

The people in the organisation are the bedrock of its success. Engaged, skilled and motivated employees ensure the company can execute on its strategy and adapt to challenges.

What this looks like in practice: Investment in development, competitive compensation, managers who are accountable for team health, willingness to slow down rather than burn people out.

Layer 2: Product Excellence

Delivering high-quality, innovative products is the core mission. Product quality directly affects customer experience and brand reputation.

What this looks like in practice: Technical debt is managed, not ignored. Releases are delayed if quality is not ready. Engineers have time for craft, not just shipping.

Layer 3: Customer Satisfaction

Happy, loyal customers drive revenue, retention and growth. Their feedback shapes the product roadmap and improves offerings.

What this looks like in practice: Support is responsive and empowered. Customer feedback reaches product teams quickly. Promises made to customers are kept.

Layer 4: Financial Health

Profitability and financial sustainability allow the company to invest in its people, products and growth initiatives.

What this looks like in practice: Sustainable unit economics. Prudent spending. Long-term thinking about capital allocation.

Layer 5: Mission Impact (Peak)

The organisation's higher purpose — whether driving innovation, creating societal value or transforming industries — inspires employees and aligns the company with long-term goals beyond profitability.

What this looks like in practice: Strategic choices are evaluated against mission alignment, not just financial return. The company is willing to forgo opportunities that conflict with its mission.

How the Pyramid Guides Decisions

The pyramid earns its keep when someone faces a genuine dilemma.

Scenario 1: Speed vs. quality

A product team is under pressure to ship a feature by quarter-end. The feature works, but it is not polished. Shipping now would satisfy customer demand and help hit revenue targets. Delaying would mean missing the quarter but delivering something the team is proud of.

Without a pyramid: This becomes a political negotiation. The loudest voice wins. Or worse, the team ships something mediocre and spends the next quarter apologising for it.

With a pyramid: Product Excellence sits below Customer Satisfaction and Financial Health. The team has explicit permission — and justification — to delay. When the VP of Sales pushes back, the answer is clear: "We do not ship work that compromises product quality. That is foundational."

Scenario 2: Cost-cutting vs. people

The company needs to reduce costs. One option is to cut development budgets, which would mean layoffs or reduced investment in employee growth. Another is to accept lower margins for a quarter while finding other efficiencies.

Without a pyramid: Finance makes the call. People feel like a line item.

With a pyramid: Engaged and Talented Workforce is the foundation. Cutting people to hit a short-term financial target would undermine the base of the pyramid. The company looks for other levers first — and if cuts are unavoidable, it communicates honestly about why and how.

Scenario 3: Customer request vs. product direction

A major customer wants a feature that would require significant engineering effort and would pull the product in a direction that does not serve other customers well. Saying yes would delight this customer and lock in revenue. Saying no risks losing them.

Without a pyramid: Customer Satisfaction and Financial Health point toward yes. But the product team has concerns. The debate drags on.

With a pyramid: Product Excellence is foundational. Building one-off features that compromise the product roadmap violates a lower layer to serve a higher one. The answer is no — with a clear explanation and perhaps a creative alternative.

Embedding the Pyramid in Goal-Setting

The Values Pyramid becomes most powerful when it shapes how goals are set across the organisation.

The principle: Every team should have goals for every layer of the pyramid.

If people are on your pyramid, every team should have metrics and objectives related to employees — engagement, development or retention. If product excellence is a value, every team should have goals related to quality, reliability or innovation. If financial health is a value, every team should understand how their work contributes to sustainable economics.

This mapping ensures two things:

-

Every value is being tended to. It is easy for teams to focus on the loudest priority and neglect foundational values. Explicit goals for each layer prevent this drift.

-

Every goal is grounded in values. When someone proposes a goal, the question becomes: "Which layer of the pyramid does this serve?" Goals that cannot answer this question are unaligned — they may not be bad, but they deserve scrutiny.

How this connects to the Alignment Stack:

The Alignment Stack describes a cascade from Metrics → Goals → Teams → Projects. The Values Pyramid sits above this cascade. It answers the question that metrics cannot: What do we actually care about, and in what order?

Metrics are how you measure progress. The pyramid is why those metrics matter. When two metrics conflict, the pyramid resolves the dispute.

In practice:

- Metrics at each layer of the pyramid become inputs to the Alignment Stack

- Goals express desired changes in those metrics

- Teams are accountable for goals at multiple layers

- Projects trace back through goals to the values they serve

This integration means that strategic alignment (the Alignment Stack) and value alignment (the Values Pyramid) reinforce each other. Work is not just connected to metrics — it is connected to the principles that make those metrics meaningful.

Adapting the Pyramid

The pyramid is meant to be stable, but it is not immutable. Business conditions change. Strategic priorities shift. The pyramid can and should be updated when circumstances require.

When to update:

- A major strategic pivot changes what the company is optimising for

- External conditions (market shifts, competitive threats, regulatory changes) require rebalancing

- The current pyramid is producing decisions that leadership disagrees with — a sign that the stated values do not match the actual values

How to update:

-

Make the change explicit. Do not quietly reprioritise. Publish the updated pyramid and explain what changed and why.

-

Communicate what is staying the same. People respond to change better when they understand what is stable. If you are elevating Financial Health this year, make clear that People and Product Excellence remain foundational.

-

Update goals to reflect the new pyramid. If Financial Health moves up, teams should expect new or elevated goals related to cost efficiency, margin improvement or revenue growth.

-

Prepare for the transition. People who made decisions under the old pyramid should not be punished for following guidance that was correct at the time.

What this prevents:

Organisations often lurch from priority to priority. One quarter it is growth. The next it is profitability. Then it is customer retention. Then it is innovation. Employees stop taking priorities seriously because they have learned that priorities are temporary.

The pyramid creates stability. When priorities shift, the shift is visible and deliberate. People understand what changed, what stayed the same and how to adjust. This is the opposite of whiplash — it is managed evolution.

Values vs. Competencies

A clarification worth making: values and competencies are related but distinct.

Values are the principles that guide what the organisation prioritises. They answer: What do we care about, and in what order?

Competencies are the behaviours and skills expected of employees. They answer: How do we expect people to work here?

Some organisations combine them. Amazon's famous leadership principles are both values ("Customer Obsession") and competencies ("Bias for Action"). This can work, but it requires care. If you call something a value but measure it like a competency, employees will optimise for being seen to demonstrate the value rather than actually living it.

The Values Pyramid is specifically about organisational priorities — what the company as a whole will trade off against what. Competencies belong in the talent framework, where Contribution Clarity and the Impact Calibration provide structure for expectations and evaluation.

That said, values and competencies should reinforce each other. If "People First" is foundational in your pyramid, you should expect to see competencies that emphasise collaboration, development of others and psychological safety. If employees are rewarded for behaviours that contradict the pyramid, the pyramid becomes fiction.

Building Your Pyramid

Step 1: Identify your values

Start by listing the values your organisation actually cares about — not the ones on the wall, but the ones that show up in decisions. Look at:

- What gets celebrated when things go well

- What gets protected when things get hard

- What leaders reference when explaining difficult trade-offs

- What would make the company unrecognisable if it were abandoned

Be honest. If financial performance consistently trumps employee wellbeing, that is your actual value hierarchy — even if the posters say otherwise.

Step 2: Stack-rank them

This is the hard part. Putting values in order requires confronting trade-offs you would rather avoid. It requires admitting that you cannot maximise everything.

Ask: "If these two values conflict, which one wins?" Work through each pair. The answers reveal your hierarchy.

Some organisations resist this step because it feels reductive. "We value all of these things!" Yes — but when they conflict, which one gives way? If you cannot answer that, you do not have a pyramid. You have a list.

Step 3: Test with real scenarios

Before publishing, test the pyramid against actual decisions the organisation has faced. Would the pyramid have produced the right answer? Does it match what leadership actually did?

If the pyramid would have produced a different answer than what happened, you have a calibration problem. Either the pyramid is wrong, or the decision was wrong. Both are worth understanding.

Step 4: Communicate and embed

Publish the pyramid. Explain the reasoning. Show how it connects to goal-setting and decision-making.

Then use it. Reference it when making trade-offs. Ask teams to connect their goals to pyramid layers. When someone makes a decision that aligns with the pyramid, call it out. When someone makes a decision that contradicts it, have the conversation.

A pyramid that lives in a slide deck is not a pyramid. It is decoration.

Learning from the Best

The companies we admire for their cultures have, whether explicitly or implicitly, built values hierarchies. Here is what we believe their pyramids look like — and how those pyramids manifest in the decisions they make.

Apple's Pyramid

- Product Excellence (foundation)

- Innovation

- Customer Experience

- Talent

- Changing the World (peak)

Apple's foundation is product excellence. Everything else — innovation, customer delight, attracting talent, changing the world — depends on building products that are genuinely great. This is not negotiable.

How it manifests:

- Products ship when they are ready, not when the calendar says so. The original iPhone was delayed. Features are cut rather than shipped half-baked.

- Premium pricing is justified by quality. Apple does not compete on cost because competing on cost would require compromising the foundation.

- Talent is attracted by the promise of working on excellent products. Apple does not need to be the highest-paying company because the work itself is the draw.

- Secrecy is protected fiercely — not for its own sake, but because surprise and delight are part of the product experience.

- "Good enough" is not good enough. Engineers and designers have permission — and obligation — to push back on anything that compromises quality.

The trade-off Apple accepts: Speed. Apple is often not first to market. They let others pioneer categories and then enter with a more refined product. This frustrates some customers and analysts, but it is the logical consequence of a product-first pyramid.

Amazon's Pyramid

- Customer Obsession (foundation)

- Long-Term Thinking

- Operational Excellence

- Frugality

- Earth's Most Customer-Centric Company (peak)

Amazon's foundation is the customer. Not the product. Not the employee. Not the shareholder. The customer. Everything else serves this foundation.

How it manifests:

- Meetings often include an empty chair representing the customer. Decisions are evaluated by their impact on customer experience.

- Long-term thinking permits short-term losses. Amazon operated at minimal profit for years, reinvesting in infrastructure and customer experience rather than rewarding shareholders.

- Operational excellence is relentless. Two-day shipping became one-day became same-day. The bar keeps rising because customer expectations keep rising.

- Frugality is a leadership principle — not because Amazon cannot afford nice things, but because money spent on perks is money not spent on customers.

- Internal tools are often spartan. Office environments are functional, not luxurious. "The door desk" is famous for a reason.

The trade-off Amazon accepts: Employee comfort and external perception. Amazon has faced criticism for demanding working conditions. Warehouse workers and corporate employees alike operate under high expectations. This is the logical consequence of a customer-first pyramid: when customer needs and employee preferences conflict, the customer wins. For people who thrive under intensity, this is energising. For others, it is unsustainable.

Netflix's Pyramid

- Talent Density (foundation)

- Freedom and Responsibility

- Candour

- Innovation

- Entertaining the World (peak)

Netflix's foundation is talent density — the belief that a team of exceptional people will outperform a larger team of average people, and that exceptional people do their best work when surrounded by other exceptional people.

How it manifests:

- The "keeper test": managers regularly ask themselves, "If this person told me they were leaving, would I fight to keep them?" If the answer is no, they receive a generous severance now rather than being managed out slowly.

- Freedom is extensive. There are no vacation policies, no travel expense limits, no approval chains for routine decisions. The assumption is that talented adults will make good choices — and if they do not, they should not be at Netflix.

- Candour is expected. Feedback flows freely, including upward. The culture memo is public. Internal disagreements are aired openly rather than suppressed.

- Innovation is enabled by freedom. Teams can take risks because they are trusted. Failures are acceptable if the reasoning was sound.

- Compensation is top of market. Netflix pays what it would cost to replace someone, not what they can get away with. This is expensive, but it is cheaper than losing talent density.

The trade-off Netflix accepts: Security and comfort. Netflix is not a family. Loyalty is not rewarded for its own sake. Someone who was exceptional five years ago but is merely good today may be let go — respectfully, with gratitude for their contributions, but let go nonetheless. This is uncomfortable. It can feel ruthless. But it is the logical consequence of a talent-first pyramid: when talent density and individual tenure conflict, talent density wins. For people who want to be challenged and who trust their own abilities, this is liberating. For people who value stability, it is terrifying.

What These Pyramids Reveal

Each of these companies has made hard choices. Apple accepts being slow. Amazon accepts being demanding. Netflix accepts being uncomfortable. These are not flaws in their cultures — they are the price of their values.

The pyramids also attract the right people. Someone who values stability will self-select out of Netflix. Someone who cannot tolerate intensity will not thrive at Amazon. Someone who wants to ship fast and iterate will find Apple's pace maddening. This is a feature, not a bug. Clear values attract people who share them and repel people who do not.

The question for your organisation is not "which of these pyramids is best?" They are best for the companies that built them. The question is: what is your pyramid? What are you willing to sacrifice, and what will you protect at all costs?

Signs the Values Pyramid Is Working

- Leaders reference the pyramid when explaining trade-off decisions

- Employees can articulate the pyramid without looking it up

- When values conflict, people know which one takes precedence

- Goals exist at every layer of the pyramid for every team

- Decisions made at lower levels of the organisation align with the pyramid

- The pyramid is updated deliberately when priorities shift, not quietly abandoned

- New hires are oriented to the pyramid and understand what it means in practice

- Performance evaluations consider how well someone embodies pyramid priorities

Signs the Values Pyramid Is Broken

- Values conflict and no one knows which wins

- Leaders invoke different values to justify conflicting decisions

- Employees cannot articulate what the company actually prioritises

- Goals focus on some pyramid layers and ignore others

- The stated pyramid contradicts observed behaviour

- Priorities shift constantly without explanation

- The pyramid exists in a slide deck but is never referenced in practice

- People are rewarded for outcomes that violate foundational values

Summary

The Values Pyramid is a model for making values operational.

Most organisations have values, but those values fail to guide decisions because they are not prioritised. When everything is equally important, nothing resolves conflict. Employees guess, escalate or play politics.

The pyramid solves this by stack-ranking values into a hierarchy where each layer supports the one above. The foundation represents what you would not sacrifice. Each ascending layer depends on the ones below. When values conflict, lower layers take precedence.

The pyramid becomes most powerful when embedded in goal-setting. Every team should have goals for every layer. This ensures that all values are tended to and that all goals are grounded in values. The pyramid sits above the Alignment Stack, answering the question that metrics cannot: What do we actually care about, and in what order?

Building a pyramid requires honesty about what the organisation actually prioritises — not what it says, but what it does. It requires the difficult work of stack-ranking, admitting that you cannot maximise everything. And it requires ongoing use: referencing the pyramid in decisions, connecting goals to layers and updating deliberately when priorities change.

Values that are not prioritised are not operational. The Values Pyramid makes them real.

Want to bring clarity to your organization?

See how Clarity Forge can help transform your team.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.