Contribution Clarity

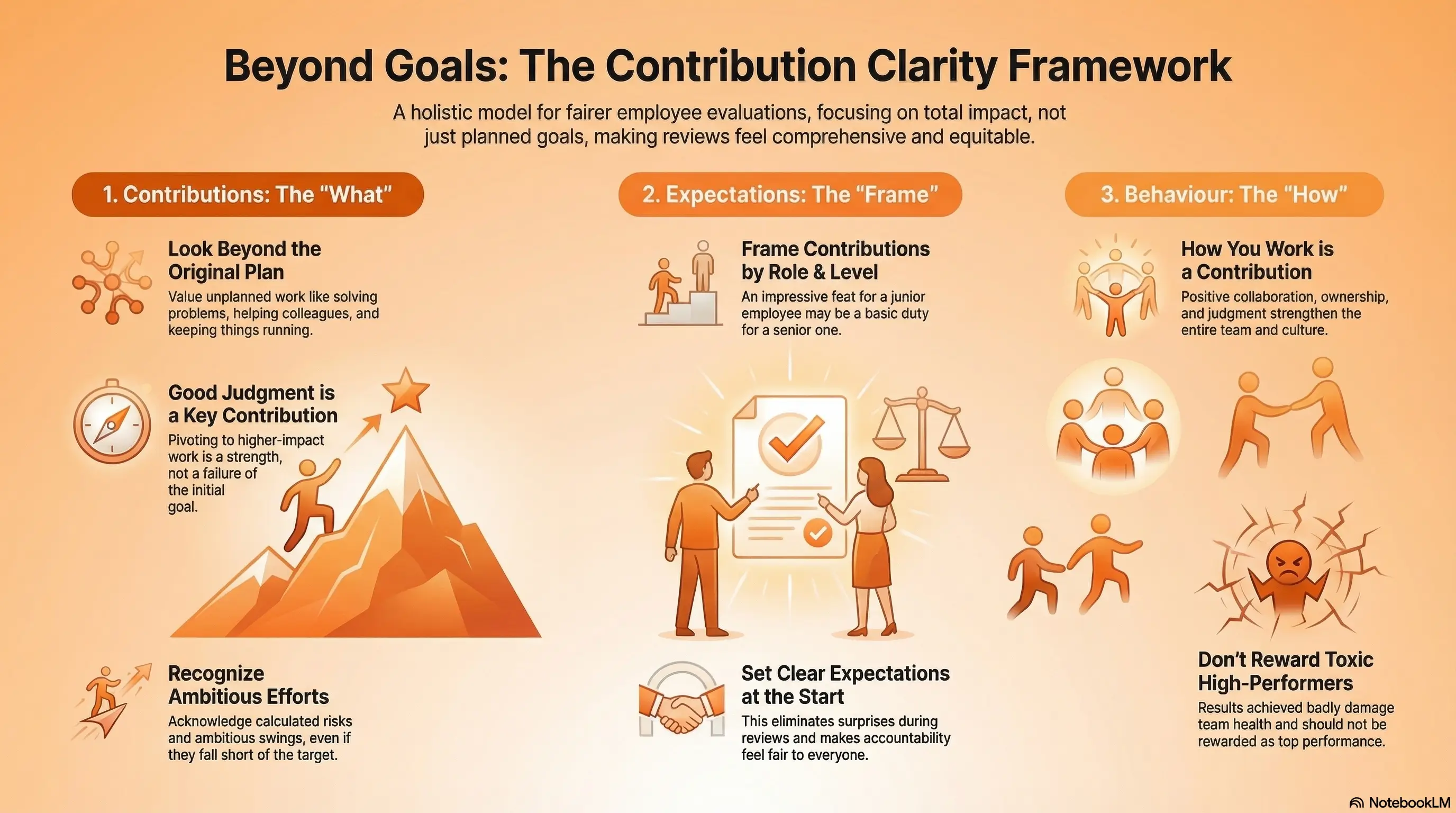

Evaluating employees fairly by seeing the full picture of what they contributed.

Purpose

Contribution Clarity is a model for evaluating employees fairly and completely. It answers a question that most managers struggle with: How do I assess someone's contributions in a way that does not feel arbitrary, to them or to me?

The answer starts with a shift in focus.

Contributions are what matter.

What did this person actually contribute during the review period? What impact did they have? What problems did they solve? What did they make possible for others?

Goals are one input, but they are not the whole picture. If someone abandoned a goal because they identified a bigger win, that is not a failure, it is good judgment, as long as it did not leave others stranded. If someone missed a goal but contributed enormously in ways their OKRs did not capture, the evaluation should reflect that.

Contribution Clarity provides a framework for seeing the full picture:

Contributions are the core of the evaluation, the impact someone had.

Expectations frame those contributions relative to role and level, what is appropriate to expect from someone in this position?

Behaviour is itself a type of contribution, how someone works affects the people around them, the culture and the organisation's long-term health.

The question is: "What did they contribute, and how does that compare to what we should expect from someone in their role?"

Why Evaluations Feel Arbitrary

Performance reviews feel arbitrary when employees do not know how they are being judged or when they find out too late.

An employee works hard for six months. They believe they are doing well. Then they receive a rating that surprises them. The manager struggles to explain exactly what was missing. The employee cannot understand how they misjudged so badly. Both leave the conversation with less trust than they started with.

This happens constantly, even in good organisations with thoughtful managers. It happens because evaluation is genuinely hard — and because most organisations have not given their managers a clear way to think about what "good" actually looks like.

Three ways evaluations go wrong:

-

Expectations were never clear. The employee optimised for what they thought mattered. The manager evaluated against what matters to them. No one discovered the gap until the review.

-

Contributions were measured too narrowly. The evaluation missed the full picture of impact — the hard problems solved, the fires extinguished, the colleagues supported, the judgment calls that avoided disasters.

-

Behaviour was ignored. The employee delivered results but burned out their teammates in the process. Or they missed targets but demonstrated exactly the growth mindset you want to see. Either way, how the work was done did not factor into the evaluation.

Contribution Clarity addresses all three.

The Framework

1. Contributions

Contributions are the substance of the evaluation. What impact did this person have?

The full picture of contribution:

Commitments kept. Did they deliver on the promises they made? This matters most when others were counting on the output — when a miss would have tripped up another team or broken a promise to a customer.

Priorities navigated well. Sometimes circumstances shift. Sometimes a bigger opportunity emerges. If someone set aside planned work to pursue higher-impact work — and did not leave anyone stranded — that is good judgment.

Impact beyond the plan. Some of the most valuable work is not planned in advance. Problems solved before they escalated. Knowledge shared with struggling colleagues. Operational work that kept things running. Help given to other teams. These are real contributions with real impact.

Difficulty and context. Not all work is equal. An employee who took on something risky and ambitious contributes differently than one who stuck to safe, predictable work — even if both delivered what they committed to.

Examples of the full picture:

The invisible contributor: Priya's main project launched two weeks late. But she also reduced page load time from 2.1s to 0.8s (improving conversion by 12%), onboarded three new engineers and caught a production issue at 11pm that would have taken down the site for an estimated 50,000 users. Looking only at the late launch misses most of her actual impact.

The strategic pivot: Marcus was three months into building a new product line when customer research revealed a bigger opportunity in an adjacent space. He made the call to pivot, knowing it meant setting aside his original plan. The pivot paid off — the new product generated $800K in revenue in its first quarter.

The safe player: Sofia delivered everything she committed to. But her commitments were not ambitious — she targeted a 10% improvement in a metric her peers were targeting for 30%. She scoped carefully to ensure she would not miss. On paper, she delivered. In practice, she contributed less than teammates who stretched further.

2. Expectations

Expectations frame contributions relative to role and level. They answer the question: what should we expect from someone in this position?

The same contribution means different things depending on who delivered it. A junior engineer who independently debugged a complex production issue has done something impressive. A staff engineer who did the same thing has done their job.

Scope of impact. What level of contribution is appropriate for this person in this role?

A junior engineer should be delivering reliably on assigned work and asking good questions. A senior engineer should be identifying problems worth solving and driving solutions across team boundaries. A staff engineer should be shaping technical direction and making the engineers around them more effective.

These are different expectations. If you have not articulated which applies to your employee, you are setting them up to optimise for the wrong things — and setting yourself up for an awkward review conversation.

Using competency frameworks.

The Talent Clarity Framework includes the idea of defining expectations relative to competency and skill levels. This can be helpful for making expectations concrete and consistent across the organisation.

For example, a competency framework might specify that Principal PMs are expected to foster org-wide collaboration, while Senior PMs are expected to drive cross-team alignment within their product area. When these expectations are written down and shared, employees know what they are aiming for — and managers have a common standard to evaluate against.

You do not need a formal competency framework to set good expectations. But if your organisation has one, use it. It makes the conversation easier.

Why setting expectations matters for accountability:

Managers often struggle to hold employees accountable. The conversation feels awkward. The feedback feels unfair. The employee gets defensive.

Most of this difficulty disappears when expectations were clear from the start. "We agreed you would be driving cross-team alignment on this project. That has not happened. What is getting in the way?" is a different conversation than "I feel like you should have been more proactive." The first is accountability. The second is a surprise.

Clear expectations make accountability feel fair — to both parties.

Examples of well-set expectations:

For a junior product manager: "At your level, I expect you to be owning the details of your feature area — writing clear specs, keeping engineering informed and surfacing blockers early. I am not expecting you to set product strategy, but I do want to see you developing opinions about where we should go and bringing them to our 1:1s."

For a senior sales rep: "You know how to close deals — that is why we hired you. This cycle I want to see you mentoring the newer reps. When you win a tough deal, share what worked. When someone on the team is struggling with an account, offer to help. Your quota matters, but so does making the team around you better."

For a manager: "Your team's output matters, but so does how you are developing your people. By the end of this cycle, I want each of your direct reports to be able to articulate their growth areas and what they are doing about them. I also need you to be more direct with David about his performance issues — we have been too gentle and it is not helping him."

3. Behaviour

Behaviour is itself a type of contribution. How someone works affects the people around them, the team's culture and the organisation's long-term health.

Two employees can deliver the same output with completely different effects on the organisation. One leaves a trail of stronger relationships, shared knowledge and teammates who learned something. The other leaves a trail of burned bridges, hoarded information and people who dread working with them again.

The output looks the same. The contribution is not.

The behaviours that matter:

-

Collaboration. Did they make others more effective? Did they share knowledge, support struggling teammates, build bridges across teams?

-

Ownership. Did they take responsibility when things went wrong? Did they follow through on commitments? Did they raise problems early or hide them until it was too late?

-

Judgment. Did they make good calls under uncertainty? Did they know when to escalate and when to decide?

-

Growth. Did they seek feedback? Did they learn from mistakes? Did they stretch beyond their comfort zone?

-

Culture. Did their presence make the team healthier? Did they model the behaviours you want to see more of?

Why behaviour must be part of evaluation:

Every performance review reinforces certain behaviours and discourages others. This is true whether you intend it or not.

If you reward results regardless of how they were achieved, you will get more of whatever behaviours produced those results — including the destructive ones. The toxic manager who burns through people but hits their numbers learns that burning through people is acceptable.

If you penalise missed targets without considering the approach, you train employees to aim low. Why take a risk that could fail when safe goals are rewarded the same way?

Acknowledge the misses that deserve recognition:

Not every failure is equal. An employee who took a calculated risk, worked hard and fell short has done something different than one who was careless or disengaged.

When someone swings big and misses, recognise the swing. "The project did not land, but you took on something hard, you executed well, and we learned a lot. That matters." This is how you build a culture where people are willing to try.

Do not reward results achieved badly:

This is the harder conversation, but it is essential.

"You delivered the project on time, and I appreciate that. But you also left a trail of frustrated colleagues and skipped steps that are now causing problems. The outcome was good. The way you got there was not. Both factor into your evaluation."

Calibration Meetings and Contribution Summaries

Calibration meetings work best when they are organised around contribution summaries.

A contribution summary is a narrative account of what someone actually contributed during the review period — their impact. It captures the full picture: commitments kept, priorities navigated, problems solved and value created.

"Sarah's main deliverable launched three weeks late. Here is what she actually contributed: she took over a failing project mid-quarter, stabilised it and got it to launch. The feature is now driving 15% of new user activations. She also onboarded two new team members and identified a compliance gap that would have cost us an estimated $200K in fines. The late launch was a direct result of being pulled onto higher-priority work."

This is a complete picture. It acknowledges the miss. It contextualises it. It captures the full impact.

Why this framing matters:

When managers know they will present contribution summaries, they start paying attention to the full picture of what their people are doing throughout the cycle — not just at review time.

When employees know they will be evaluated on contributions, they make better decisions. They feel permission to pivot when circumstances change. They invest in work that matters even if it was not part of the original plan.

When calibration discussions centre on contributions, the comparisons become more meaningful. "Sarah and James are both rated as 'exceeds expectations' — let me tell you what each of them contributed" is a rich conversation.

What a contribution summary includes:

- Key contributions during the period — commitments delivered, problems solved, impact created

- Quantified impact where possible — revenue generated, costs saved, efficiency gains, incidents prevented

- Context that affected the work — shifting priorities, unexpected challenges, circumstances that made things harder or easier

- Contributions beyond the plan — operational work, support given to others, invisible effort

- How the work was done — behaviours that strengthened or weakened the team

- Assessment relative to expectations — how does this compare to what we should expect from someone at this level?

Examples of contribution summaries:

A TPM summary: "James's team delivered $4.2M in cost savings this year through infrastructure optimisation and vendor renegotiations — roughly 10x what the team costs. He shipped two of his three major initiatives on schedule; the third was descoped when we pivoted away from that product line. Beyond his planned work, he led the incident response for the March outage and built the post-mortem process we now use company-wide."

A product manager summary: "Sarah's main deliverable launched three weeks late. Here is what she actually contributed: she took over a failing project mid-quarter, stabilised it and got it to launch. The feature is now driving 15% of new user activations. She also onboarded two new team members and identified a compliance gap that would have cost us an estimated $200K in fines. The late launch was a direct result of being pulled onto higher-priority work."

An engineer summary: "Priya delivered two of her three planned initiatives. The third — the API redesign — was abandoned when we decided to buy instead of build. Her major contributions: she reduced average page load time from 2.1s to 0.8s (measurably improving conversion), she mentored two junior engineers through their first production deployments and she caught a security vulnerability in code review that could have exposed customer data. She also carried more than her share of on-call rotations when the team was short-staffed."

The discipline of writing contribution summaries forces managers to see the full picture. The discipline of presenting them in calibration forces honest comparison across the team.

Putting It Into Practice

At the start of the cycle:

- Have an explicit expectations conversation with each team member

- Define the scope of contribution appropriate for their level

- Name the behaviours you are looking for

- Document what you agreed so you can both reference it later

During the cycle:

- Keep a running log of contributions — do not trust your memory

- Have regular check-ins about how work is being perceived (see: [Impact Calibration])(https://www.clarityforge.ai/frameworks/impact-calibration "Impact Calibration")

- Revisit expectations when priorities shift

- Note behaviours, not just outputs

At review time:

- Write a contribution summary for each team member

- Evaluate contributions against the expectations you set

- Include behaviour as a type of contribution

- No surprises — if you have been talking throughout, the review confirms what both already know

In calibration meetings:

- Present contribution summaries

- Compare contributions across the team

- Use expectations to frame what "good" looks like at each level

- Discuss behaviour as part of the contribution picture

Signs Contribution Clarity Is Working

- Employees know what is expected of them before the cycle begins

- Evaluations consider the full picture of contribution

- Behaviour is recognised as a type of contribution — how work is done matters

- Reviews hold no surprises because expectations were clear and calibration happened throughout

- Employees who pivot to higher-impact work are rewarded for good judgment

- Employees who aim high and fall short are recognised for their ambition

- Employees who deliver through toxic behaviour are not rewarded as top performers

- Calibration meetings centre on contribution summaries

- Managers can articulate specifically what someone contributed and why it mattered

- Evaluations feel fair — even when the news is hard to hear

Signs Contribution Clarity Is Broken

- Employees are surprised by their evaluations

- Evaluations miss the full picture — only some contributions count

- Pivoting to higher-impact work is penalised rather than rewarded

- Behaviour is never discussed — only outputs matter

- Toxic high performers are celebrated while collaborative contributors are overlooked

- Employees play it safe to avoid the risk of falling short

- Expectations are only articulated at review time, retroactively

- Calibration meetings lack substance and context

- Managers cannot explain what someone actually contributed

- Evaluations feel arbitrary or political

Summary

Contribution Clarity is a model for evaluating employees fairly and completely.

Contributions are the core of the evaluation — the impact someone had. Commitments kept matter, especially when others were depending on them. But contributions include much more: problems solved, colleagues supported, operational work that kept things running and good judgment about when to pivot. The question is: "What impact did they have?"

Expectations frame contributions relative to role and level. The same contribution means different things depending on who delivered it. Clear expectations — set at the start of the cycle, ideally grounded in competency frameworks — make evaluation feel fair and make accountability possible.

Behaviour is itself a type of contribution. How someone works affects the people around them and the organisation's long-term health. Every evaluation reinforces certain behaviours. Make sure you are reinforcing the ones you want to see more of.

Calibration meetings should be organised around contribution summaries. When managers present narratives of what their people actually contributed — quantified where possible, contextualised and framed by expectations — the conversation becomes richer and the comparisons more meaningful.

The goal is evaluation that feels fair because the criteria were clear, the assessment was complete and the conversation was honest.

Most employees want feedback. They want to know where they stand. Contribution Clarity gives you a way to tell them.

Want to bring clarity to your organization?

See how Clarity Forge can help transform your team.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.