Impact Calibration

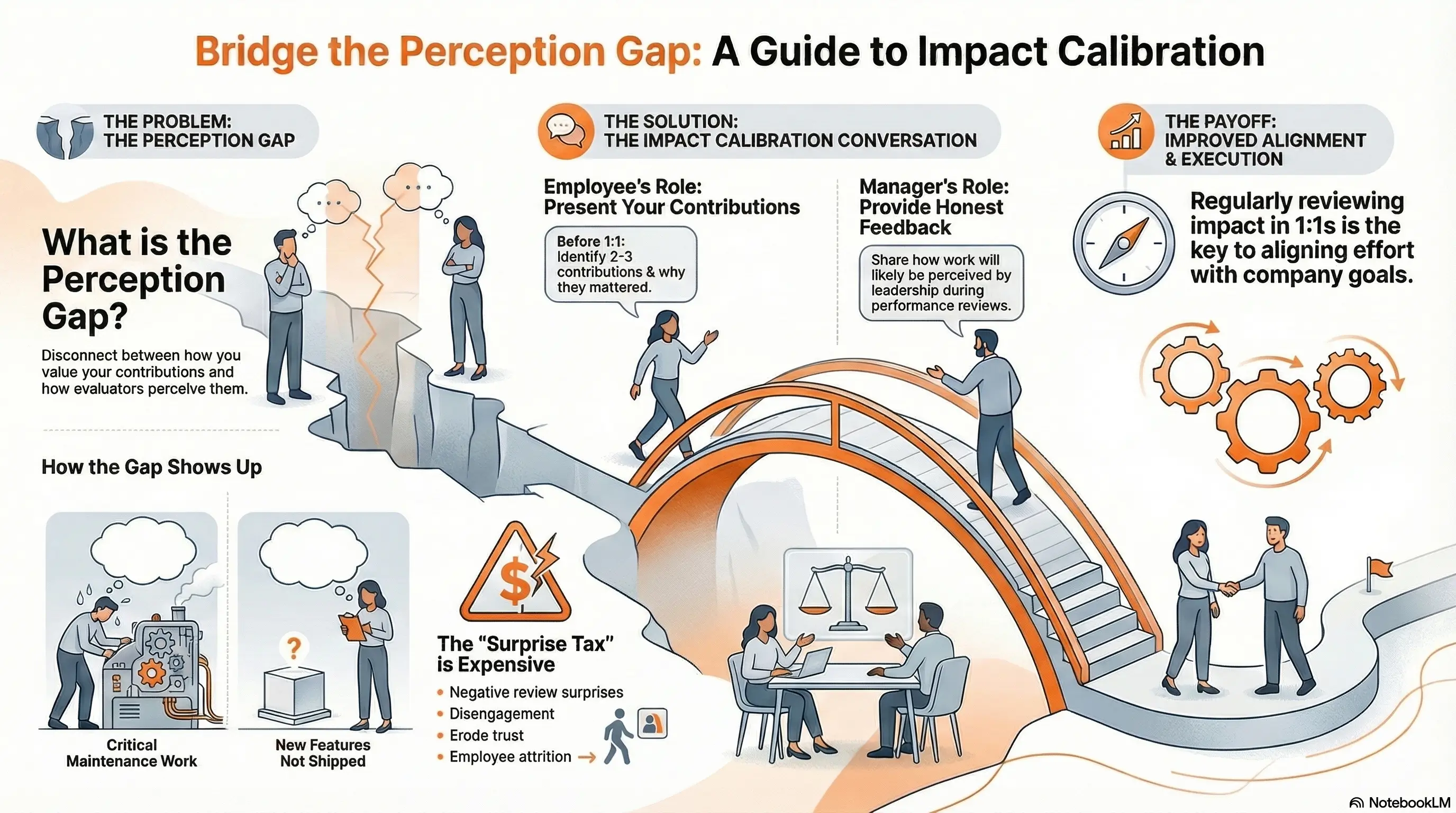

Closing the gap between how you see your contributions and how evaluators see them

Purpose

The Impact Calibration is a model for closing the perception gap between the work employees believe they are doing and how that work is seen by the people who evaluate them. It answers a question that most professionals avoid until it is too late: Does my manager see my contributions the way I do?

The answer is almost always no. Not because managers are unfair or employees are deluded, but because they are looking at the same work from different vantage points, with different information and different definitions of what matters right now.

This gap is normal. Leaving it unexamined is not.

The Impact Calibration creates a habit of surfacing these differences early — in regular, low-stakes conversations — rather than discovering them at review time when the consequences are real and the opportunity to adjust has passed.

The Perception Gap

Every employee carries a mental model of their own value. It is built from the work they do, the effort they invest, the problems they solve and the contributions they believe they are making. This model feels accurate because they are closest to the work.

Every manager carries a different mental model of that same employee. It is built from what they observe in meetings, what they hear from others, what shows up in deliverables and how the employee's work compares to what the team needs right now. This model also feels accurate because managers see the broader context.

These two models are never identical. The question is how different they are — and whether anyone notices before it matters.

The perception gap shows up in predictable ways:

- An employee spends weeks on work they consider foundational; their manager sees someone who "didn't deliver"

- An employee believes they are driving alignment across teams; their manager sees someone who is "always in meetings" rather than making decisions

- An employee invests heavily in mentoring junior colleagues; the review committee sees someone whose individual output fell short

- An employee takes on unglamorous maintenance work; leadership notices only the people shipping new features

In none of these cases is the employee wrong about the value of their work. The work may genuinely matter. But value that is invisible to evaluators is value that does not count when decisions are made about ratings, promotions and opportunities.

The Impact Calibration exists to make these gaps visible while there is still time to do something about them.

The Surprise Tax

Most organisations discover perception gaps at the worst possible moment: during performance reviews or promotion decisions.

An employee who has spent a year believing they were exceeding expectations learns they are rated as "meeting expectations." Someone who was confident they were ready for promotion learns they were never seriously considered. A high performer who thought they were valued discovers their manager cannot articulate what they actually contributed.

These surprises are not just uncomfortable. They are expensive.

The cost of a review surprise:

- Weeks or months of disengagement while the employee processes what happened

- Erosion of trust between employee and manager that may never fully recover

- Reduced discretionary effort as the employee recalibrates their investment in the role

- Attrition, often of exactly the people you least want to lose

- Reputation damage as the story spreads to peers

Compare this to what it costs to make calibration a regular part of the 1:1 conversations managers should already be having.

The maths is not close. Calibration is not extra work — it is doing the work that 1:1s are meant to do. Managers and employees who treat their regular conversations as calibration opportunities are not adding meetings. They are making the meetings they already have dramatically more valuable.

Why Both Sides Need This

The Impact Calibration is not something managers do to employees or employees extract from managers. Both parties benefit, and both have blind spots that the conversation addresses.

What Employees Miss

Employees are closest to their own work, which means they see effort that no one else sees. They know how hard the problem was. They know what they sacrificed. They know what would have happened if they had not stepped in.

But proximity creates blind spots:

- Context about priorities. The work may be valuable in the abstract but misaligned with what the organisation needs right now. An employee cannot always see this from where they sit.

- Relative comparison. Employees rarely know how their contributions compare to peers at the same level. Managers see across the team; employees see only their own work.

- What evaluators actually value. The criteria that matter in calibration discussions are often implicit. Employees optimise for what they think matters, which may not match what actually matters.

- How the story will be told. When a manager advocates for an employee in a calibration or promotion discussion, they need a clear, compelling narrative. If the employee has not helped construct that narrative, the manager may struggle to tell it — or tell it wrong.

What Managers Miss

Managers see outcomes and behaviours, but they rarely see the full picture of what produced them.

- Invisible effort. Problems solved quietly, fires extinguished before they spread, help given to struggling colleagues — these contributions are often invisible unless someone surfaces them.

- The cost of asks. Managers often underestimate how much time and energy their requests consume. A "quick project" may have displaced a week of planned work.

- What the employee is optimising for. Without explicit conversation, managers may misinterpret an employee's choices. What looks like lack of initiative may be deliberate prioritisation. What looks like overreach may be an attempt to demonstrate readiness for promotion.

- Skills being developed. An employee may be deliberately stretching into new areas. Without context, the manager sees only the rough early performance, not the investment in growth.

The Impact Calibration creates space for both parties to share what they see and learn what they are missing.

Calibration as an Alignment Mechanism

The Impact Calibration is not just about individual performance. It is one of the most effective tools for driving alignment across the organisation.

When employees regularly discuss their contributions with their managers, something else happens: they develop a clearer understanding of what the organisation actually values. They learn which goals matter most right now. They discover how their work connects — or fails to connect — to the metrics and priorities that leadership cares about.

This is alignment built from the ground up.

Alignment with company goals. Calibration conversations force the question: "How does this contribution connect to what the organisation is trying to achieve?" An employee who cannot answer this question has learned something important. A manager who cannot explain the connection has revealed a gap in their own communication. Either way, the conversation surfaces misalignment that would otherwise remain hidden.

Alignment with team priorities. Teams drift. The work that felt urgent three months ago may no longer be the priority. Calibration conversations create regular checkpoints where employees and managers can verify that individual effort is still pointed in the right direction. When it is not, the adjustment happens in weeks rather than quarters.

Alignment with project outcomes. Projects succeed when contributors understand not just what they are building but why it matters. Calibration conversations reinforce this connection. An employee who hears "this project is critical to our retention metric" understands the stakes differently than one who is simply assigned tasks.

Alignment across teams. When managers across an organisation are having calibration conversations with their reports, they develop a shared understanding of what "good" looks like. They hear the same questions, surface the same gaps and calibrate their own expectations against each other. This consistency does not happen automatically — it emerges from the discipline of regular, honest conversation.

The Impact Calibration works at the individual level, but the benefits compound at the organisational level. Teams where calibration is a habit are teams where people understand the strategy, see how their work connects to it and adjust quickly when priorities change.

The Calibration Conversation

The core of the Impact Calibration is making perception alignment a regular part of manager-employee 1:1s. Not a separate meeting. Not an additional process. Just a different focus for conversations that should already be happening.

The question at the heart of every calibration conversation is simple: What have I contributed recently, and how do you think it will be perceived?

This is not a status update. It is not rushing through an agenda to check a box. It is a deliberate examination of the gap between self-perception and external perception — and it belongs at the centre of effective 1:1s, not at the margins.

The Employee's Preparation

Before each conversation, the employee should identify two or three contributions they believe were meaningful. For each one:

- What was it? A concrete description of the work.

- Why did it matter? The outcome or value it produced.

- Who saw it? Whether the impact was visible to the manager, peers, leadership or only to the employee.

- How does it connect? Which goals, metrics or team priorities it served.

This is not about building a case or selling yourself. It is about creating the raw material for an honest conversation.

The Manager's Role

The manager's job is to provide calibration — to share how they see the same contributions and, critically, how they believe others will see them.

For each contribution the employee raises:

- Do I see it the same way? If not, what is different about my perspective?

- How will this land at review time? Will it be seen as significant, expected or insufficient?

- What context is the employee missing? Are there priorities, comparisons or expectations they may not be aware of?

- What would make this more valuable? Is there a way to increase the visibility or impact of this work?

The manager should be honest, even when the honest answer is uncomfortable. A manager who only validates is not calibrating — they are setting up a future surprise.

Calibrating Against Expectations

Raw contributions do not exist in a vacuum. They are evaluated against expectations — what someone at this level, in this role, should be delivering.

Most organisations define these expectations through competencies: the skills and behaviours that matter for success. Stakeholder management. Technical depth. Strategic thinking. Communication. Execution. The specific competencies vary by role and organisation, but the principle is consistent: there is a defined set of things that matter, and performance is assessed against them.

Effective calibration conversations make these expectations explicit:

- What competencies matter for this role? If the organisation has defined competencies, both employee and manager should know them. If the organisation has not, the manager should articulate what they believe matters most.

- What does "good" look like at this level? Expectations scale with seniority. A junior employee demonstrating stakeholder management looks different from a senior leader doing the same. Calibration requires shared understanding of level-appropriate performance.

- How does this contribution map to competencies? When an employee surfaces a contribution, part of the calibration is identifying which competency it demonstrates — and whether it demonstrates it at the expected level.

- Where are the gaps? Calibration is not just about validating strengths. It is about identifying where contributions are falling short of expectations, while there is still time to adjust.

This framing transforms calibration from a subjective conversation ("do you think I'm doing well?") into an objective one ("am I meeting the defined expectations for my role?"). It also gives employees agency: if the expectations are clear, they can deliberately develop the competencies that matter.

Clarity Forge's Grow module is designed around this structure — defining competencies, setting expectations by role and level and tracking contributions against them. But the principle applies regardless of tooling: calibration is more effective when both parties know what "good" looks like.

The Conversation Flow

A calibration conversation might go like this:

Employee: "I spent the last two weeks refactoring the authentication module. The code was brittle, and I think this will save us significant debugging time over the next year."

Manager: "I know you put a lot of work into that, and I agree the code needed attention. But I want to be honest with you about how this will be perceived. Right now, leadership is focused on the feature roadmap. At review time, the question will be 'what did this person ship?' If the answer is 'they refactored auth,' that is going to land as maintenance work, not as a major contribution. It is not that the work was wrong — it is that it will not carry the weight you might expect."

Employee: "That's frustrating, but useful to know. What would you suggest?"

Manager: "A couple of things. First, let's make sure the impact is documented somewhere visible — maybe a brief write-up on the eng wiki showing the before and after. Second, let's make sure the next few weeks include something more visible on the roadmap. I don't want your quarter to be defined by work that leadership will not see."

This conversation took five minutes. It surfaced a perception gap and produced a concrete adjustment. Without it, the employee might have continued heads-down on valuable-but-invisible work for months, only to be surprised by a mediocre review.

When You Disagree

The calibration conversation will sometimes reveal genuine disagreement. The employee believes their work was significant; the manager sees it differently. Or the manager's assessment of "how this will land" feels unfair to the employee.

This is not a problem. It is the point.

Disagreement surfaced early is an opportunity. Disagreement surfaced at review time is a crisis.

Productive Disagreement

When perspectives differ, both parties should seek to understand the gap:

For the employee:

- "Help me understand what would have made this more valuable in your eyes."

- "Is this a visibility problem or a substance problem? Would the same work be valued more if others had seen it?"

- "What am I missing about the current priorities that makes this land differently than I expected?"

For the manager:

- "I hear that you see this differently. Tell me more about why this felt significant to you."

- "Is there context I am missing about what this work required or what it prevented?"

- "If you were making the case for this contribution to my manager, what would you say?"

The goal is not to reach agreement. It is to reach understanding. Sometimes the employee will realise they misjudged the value of their work. Sometimes the manager will realise they undervalued it. Sometimes both will understand each other's perspective without changing their own.

All of these outcomes are better than silence.

When the Gap Persists

If repeated calibration conversations reveal a persistent gap — the employee consistently values contributions that the manager does not — this is important information.

It may indicate:

- A mismatch between the employee's strengths and the team's current needs

- A mismatch between the employee's aspirations and the role they are in

- A difference in values that will continue to create friction

These are hard conversations, but they are better had explicitly than allowed to fester. An employee who learns early that their preferred type of work is not valued in their current context can make informed decisions — seek a different role, adjust their approach or accept the trade-off knowingly.

The Evidence Habit

Calibration conversations require raw material. Without it, both parties are working from memory — which is unreliable and biased toward recent events.

The solution is simple: employees should keep a running log of contributions they believe are meaningful. Not a polished document. Not a performance journal. Just a lightweight habit of noting "things I did that I think mattered."

What to capture:

- What you did (concrete and specific)

- What outcome it produced or what problem it solved

- Who was involved or affected

- Any feedback you received

When to capture it:

- At the end of each week, spend five minutes adding to the log

- Immediately after completing something significant

- When you receive positive feedback (or negative feedback you learned from)

This log serves multiple purposes:

- It provides material for calibration conversations

- It reduces recency bias in self-reviews

- It helps the manager build the case for you when the time comes

- It reveals patterns over time — where you are investing and whether that investment is valued

Clarity Forge's Grow module provides a structured place to capture these notes, making them available when calibration and review discussions happen. But the habit matters more than the tool. A shared document, a personal notebook or a weekly email to yourself will work if the habit is consistent.

Beyond the Manager

The Impact Calibration focuses on the employee-manager relationship, but perception gaps exist more broadly.

Peers form impressions of your work that influence their willingness to collaborate, recommend you for opportunities or support your promotion. A peer who sees you as "always asking for help" or "hard to work with" carries that perception into skip-level conversations and calibration discussions.

Skip-level managers and leadership have limited visibility into your work. What they see is filtered through your manager, through occasional presentations and through reputation. If they have formed an impression of you — positive or negative — you may not know it.

Cross-functional partners interact with you in a narrow context. They may see you only in meetings where you are advocating for your team's interests. The impression they form may not match your self-perception.

The calibration conversation can extend to these relationships:

- "How do you think the design team perceives my collaboration with them?"

- "What is the leadership team's impression of me, if any?"

- "Is there anyone whose perception of me I should be concerned about?"

Managers often have visibility into these dynamics that employees lack. Surfacing them early allows for course correction before peripheral perceptions become fixed.

The Manager as Advocate

There is a selfish reason for managers to invest in calibration conversations: it makes them better at their job.

When calibration or promotion time comes, managers must advocate for their people. They sit in rooms with other managers and make the case for ratings and promotions. The managers who succeed in these conversations are the ones with evidence, specifics and a clear narrative.

A manager who has regular calibration conversations arrives at review time with:

- A detailed understanding of each employee's contributions

- Concrete examples that can withstand scrutiny

- A narrative that has been tested and refined over months

- Confidence that there will be no surprises — from the employee or about the employee

A manager who skips these conversations arrives with vague impressions and a scramble to reconstruct six months of work from memory. They are less effective advocates. Their people get worse outcomes.

Calibration conversations are not extra work for managers. They are preparation for the work managers are already accountable for.

Calibration in Practice: Examples

The Invisible Firefighter

Situation: A senior engineer spends three weeks stabilising a production system after a series of incidents. The work is intense, stressful and critical. Without it, customers would have been affected.

Employee's view: "I saved us. This was my most important contribution of the quarter."

Likely perception at review time: "Kept the lights on. Expected at this level."

What calibration surfaces: The manager explains that incident response, while critical, is table stakes for senior engineers. It prevents disaster but does not demonstrate growth or leadership. The employee learns that to be perceived as "exceeding expectations," they need to show impact beyond reactive work — preventing incidents, improving systems or leading others.

Adjustment: The employee documents what caused the instability and proposes systemic fixes. This transforms "I fought fires" into "I identified a pattern and improved our reliability posture." Same work, different narrative, different perception.

The Meeting Martyr

Situation: A product manager attends 30+ hours of meetings per week, believing they are essential for cross-functional alignment.

Employee's view: "I am the connective tissue of this organisation. Nothing would ship without my coordination."

Likely perception at review time: "Always in meetings. Not clear what they actually produce."

What calibration surfaces: The manager shares feedback from peers: the PM is seen as a meeting scheduler, not a decision-maker. Their presence in meetings is not producing the alignment they believe it is. Other PMs with fewer meetings are shipping more.

Adjustment: The employee audits their meeting load, identifies which meetings they attend out of habit rather than necessity and reallocates time to producing artefacts (specs, roadmaps, decisions) that demonstrate tangible output. They also start delegating meeting attendance to create visibility for others.

The Generous Mentor

Situation: A senior individual contributor spends 20% of their time mentoring junior team members. The juniors are growing noticeably.

Employee's view: "I am multiplying myself. The juniors I have mentored will pay dividends for years."

Likely perception at review time: "Individual output is below peers at this level."

What calibration surfaces: The manager agrees that the mentorship is valuable but warns that the promotion committee will compare the employee's individual output to peers who did not make this investment. Mentorship is valued, but not as a substitute for delivery.

Adjustment: Several options emerge. The employee could reduce mentoring and increase individual output. Alternatively, the manager could formalise the mentoring role — making it an explicit expectation rather than discretionary investment. Or the employee could accept that they are trading near-term advancement for a different kind of contribution, knowingly rather than naively.

The Strategic Thinker

Situation: A mid-level employee produces a detailed analysis of market trends with recommendations for product strategy. They share it with their manager and several executives.

Employee's view: "I am operating above my level. This demonstrates strategic thinking and readiness for promotion."

Likely perception at review time: "Produced an unsolicited strategy doc. Unclear if it influenced anything."

What calibration surfaces: The manager explains that strategy documents from ICs are often received as overreach unless explicitly requested. The executives appreciated the initiative but have not changed any plans based on it. Impact is measured by outcomes, not artefacts.

Adjustment: The employee learns to connect strategic thinking to implementation. Instead of a standalone document, they propose a specific experiment to test one hypothesis. If it works, they have evidence. They also learn to socialise ideas before documenting them, building support rather than surprising stakeholders.

For Leaders: Making Calibration Meetings Count

The calibration conversations described above happen between individual employees and their managers. But there is another kind of calibration that happens at the leadership level: the meetings where managers come together to compare employees, assign ratings and make promotion decisions.

These meetings are often the final checkpoint before reviews are delivered. They are also one of the most underutilised opportunities in talent management.

The Problem with Calibration Meetings

Most calibration meetings are box-checking exercises. Managers present their ratings, defend the obvious outliers and reach consensus quickly. The goal is to get through the list, not to develop the people on it.

The result: managers leave with ratings but little else. They have no new information to bring back to their reports. The meeting consumed hours of leadership time and produced nothing beyond what each manager walked in with.

This is a waste.

Calibration Meetings as Feedback Engines

The best calibration meetings produce two outputs: fair ratings and actionable feedback.

When a room full of managers discusses an employee, something valuable happens. Perspectives emerge that no single manager could access alone:

- A peer manager mentions that the employee is difficult to collaborate with across team boundaries

- A skip-level leader shares that the employee made a strong impression in a recent presentation

- Someone raises a concern about the employee's judgment in a specific situation

- The group discusses why one employee is rated higher than another who appears similar on paper

This is gold. It is exactly the kind of multi-perspective feedback that employees rarely receive and desperately need.

But in most organisations, this feedback never leaves the room. The conversation happens, the ratings are finalised and the insights evaporate.

Managers have a responsibility to harvest this feedback. When someone says "we're ranking Sarah higher than James because of how she handled the platform migration," that is feedback worth bringing back. When a concern is raised about an employee's visibility or collaboration, that is feedback worth surfacing — carefully, at a high level — in subsequent 1:1s.

This requires intentionality. Managers should enter calibration meetings with a notebook and leave with specific observations to share with their reports. Not verbatim quotes. Not attribution. But the substance: "Here's what I learned about how you're perceived, and here's what would change that perception."

Beyond Rating: Developmental Calibration

The most sophisticated leadership teams separate calibration-for-rating from calibration-for-development.

Rating calibration happens on a cycle — quarterly, semi-annually or annually — driven by the performance review process. The goal is fair and consistent assessment.

Developmental calibration happens more frequently and with a different purpose. Leadership teams come together to discuss their people not to assign ratings but to share observations, identify growth opportunities and coordinate investment in talent.

Questions for a developmental calibration session:

- Who are our highest-potential people and what are we doing to accelerate their growth?

- Who is struggling, and do we understand why?

- Where are we seeing patterns — skills gaps, engagement issues, collaboration friction — that suggest systemic problems?

- What feedback has surfaced about specific individuals that their manager should know?

- Who is ready for more responsibility, and what would test that readiness?

These conversations do not produce ratings. They produce insight — insight that managers can bring back to their calibration conversations with employees.

The Feedback Loop Completes

When leaders treat calibration meetings as feedback opportunities and bring that feedback into ongoing 1:1 conversations, the loop closes:

- Employees share their perceived contributions with their manager (individual calibration)

- Managers share how those contributions are perceived, including by peers and leadership (individual calibration informed by organisational perspective)

- Leaders discuss employees across teams and surface observations that no single manager could see (leadership calibration)

- Managers bring relevant feedback back to employees (individual calibration enriched by leadership input)

This is how organisations develop people systematically rather than accidentally. It requires more from leaders than the typical calibration meeting asks. But the return — employees who understand how they are perceived across the organisation and what would change that perception — is worth the investment.

Signs Impact Calibration Is Working

- Employees can accurately predict how their manager perceives their contributions

- Review discussions hold no surprises for either party

- Employees adjust their approach based on calibration feedback, not just validation

- Managers can articulate each employee's contributions with specificity and evidence

- Disagreements about perception surface in regular conversations, not in review meetings

- Promotion cases are built over months through ongoing dialogue, not assembled retroactively

- Employees understand not just what they did but how it connects to competencies and expectations

- 1:1 conversations naturally include discussion of contributions and how they will be perceived

- Leadership calibration meetings produce actionable feedback that flows back to employees

- Employees understand how they are perceived not just by their manager but across the organisation

Signs Impact Calibration Is Broken

- Employees are surprised by review ratings or promotion decisions

- Managers struggle to articulate what their reports contributed

- 1:1 conversations focus on status updates and logistics rather than contributions and perception

- Calibration conversations become superficial check-ins rather than honest exchanges

- Employees hear only validation, never redirection

- The same perception gaps appear repeatedly without resolution

- Review time becomes a scramble to reconstruct months of work from memory

- Employees optimise for what they think matters rather than what actually matters

- Competencies and expectations exist on paper but are never discussed in practice

- Leadership calibration meetings produce ratings but no actionable feedback

- Insights from cross-team discussions never reach the employees they concern

Summary

The Impact Calibration is a discipline for closing the perception gap between self-assessed contributions and how those contributions are seen by evaluators.

It is built on a simple insight: employees and managers are looking at the same work from different vantage points. Without explicit conversation, these perspectives diverge — sometimes dramatically. The divergence surfaces at review time as surprise, disappointment and eroded trust.

The solution is making calibration a regular part of the 1:1 conversations managers should already be having. Employees surface what they believe they have contributed. Managers share how that work is likely to be perceived — against defined competencies, role expectations and organisational priorities. These are not performance reviews. They are perception checks — low-stakes opportunities to identify gaps while there is still time to close them.

The benefits extend beyond individual performance. Calibration conversations drive alignment with company goals, team priorities and project outcomes. They create a shared understanding of what "good" looks like across the organisation. And when leaders treat their own calibration meetings as feedback opportunities, the insights that emerge can flow back to employees, closing the loop between individual effort and organisational perception.

Both parties benefit. Employees gain visibility into how their work is valued and what adjustments would increase their impact. Managers gain the specificity and evidence they need to advocate effectively for their people. Leaders gain confidence that their teams understand priorities and are developing in the right direction.

The cost is trivial: a shift in how existing conversations are conducted. The alternative — months of misaligned effort followed by a surprise that damages trust and engagement — is far more expensive.

Calibration is not about gaming the system. It is about making sure the system sees you clearly. The work still has to be good. But good work that is invisible, misunderstood or misaligned with expectations does not count. Impact Calibration makes sure it does.

Want to bring clarity to your organization?

See how Clarity Forge can help transform your team.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.