Portfolio Discipline

A Clarity Framework for optimizing project portfolios.

Purpose

Portfolio Discipline is a model for actively managing the work an organisation is doing — and more importantly, the work it should stop doing.

It answers a question that most organisations avoid: What should we stop investing in so we can invest more in what matters most?

This sounds straightforward. In practice, it is remarkably hard. Projects that should have ended months ago continue indefinitely. Teams that were stood up three years ago to solve a particular problem are still solving that problem — writing OKRs every six months, prioritising within their scope, making steady progress — while the landscape has shifted around them. The work they are doing is not worthless. It has value. But when compared to other problems the organisation could be solving, it might be a tenth as important.

No one is lying. No one is acting in bad faith. The problem is structural: individual managers are not incentivised to give up their people. Doing so feels like sabotaging their own career. So the only way this works is if leadership teams are transparent about their investments and make portfolio management a team sport — a shared responsibility rather than an individual sacrifice.

The result of not doing this is an organisation where high-calibre people work on low-impact projects while critical initiatives cannot find the talent they need. Everyone is busy. The numbers barely move.

Portfolio Discipline provides a framework for making investments visible, creating the conditions where rebalancing becomes possible and building the organisational muscle to do it continuously.

The Structural Problem

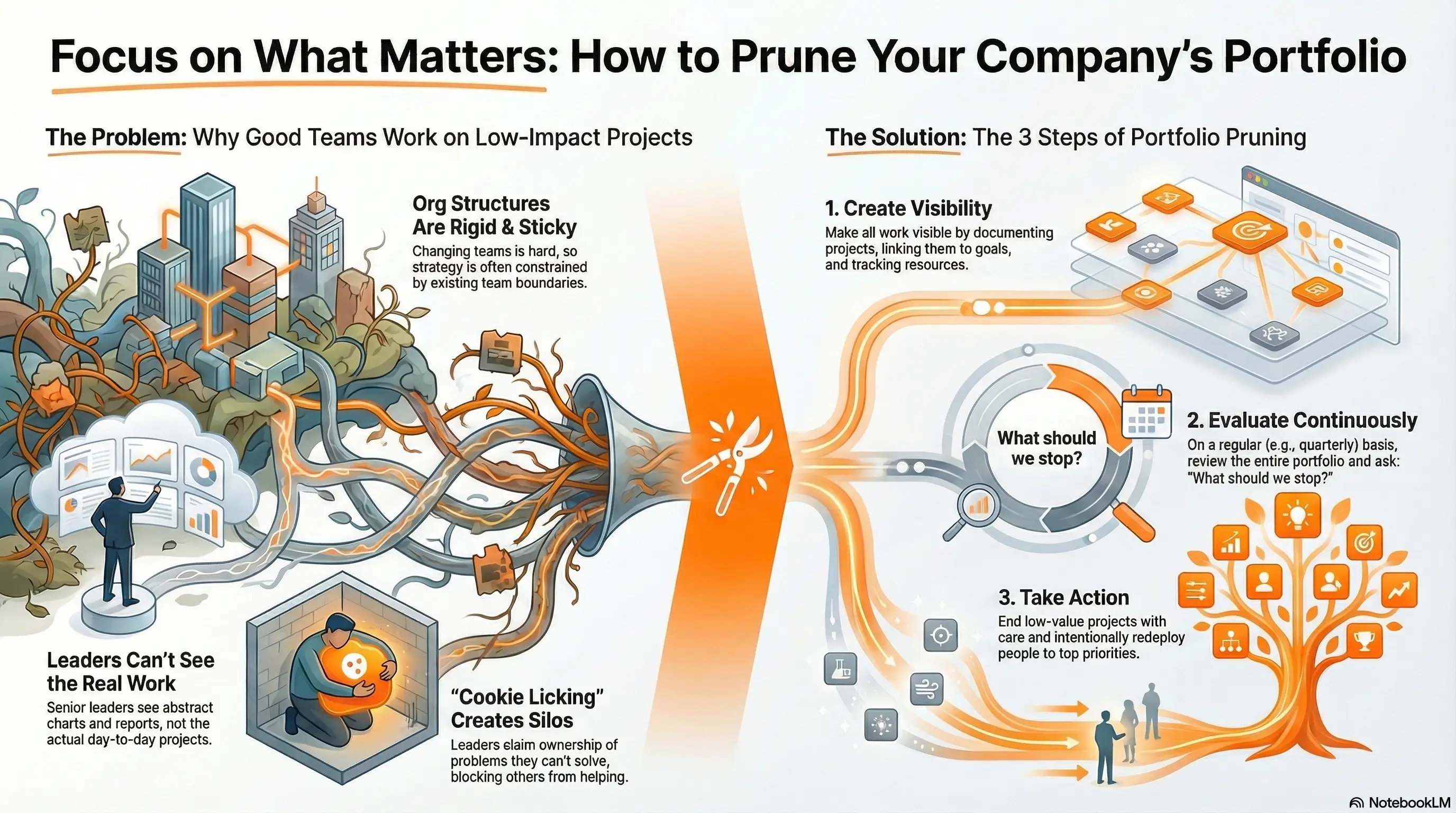

Why do smart, well-intentioned leaders preside over portfolios full of relatively low-value work? Because the forces that perpetuate work are structural — baked into how organisations operate.

Organisational rigidity

Most organisations allocate costs, budgets and people through the org structure. HR systems track headcount by team. Finance tracks spend by department. Capacity planning assumes stable team boundaries.

This makes the org structure sticky. Changing it requires coordination across multiple functions — HR, finance, facilities, IT. The administrative friction is enormous. Even when everyone agrees that a project should end and the team should be redeployed, making it happen requires a level of effort that discourages action.

The result: strategy and prioritisation happen within the constraints of the existing org structure rather than challenging it. Leaders optimise within their scope because crossing boundaries is expensive. A director will agonise over which of their projects to prioritise, but rarely ask whether their entire team should be doing something different.

Leaders cannot see the work

Once a manager has dozens of people reporting to them — let alone hundreds or thousands — they cannot possibly know what work is being done. They know they have a certain number of direct reports, and that those people are managing complexity in their space. But the actual projects, the day-to-day effort, the connection between activity and outcomes — this is invisible.

What senior leaders see are layers of abstraction. They see org charts and headcount numbers. They see high-level status updates that have been filtered through multiple layers of management. They see dashboards that report on metrics but not on the work that supposedly moves them.

This is not a failure of leadership. It is a structural feature of scale. The only people who know the work are the people doing it — and they rarely have visibility into whether their work is the highest-value use of the organisation's capacity.

Scoping constrains strategy

Static org structures create information silos. Teams optimise within their scope. They do not share tools they have built. They do not surface ideas that belong to someone else's domain. They do not raise their hand when they see higher-value problems outside their mandate.

Actually, that last point is not quite right. Many people do see bigger problems they want to solve. They have ideas. They have energy. They would gladly move to work on something more impactful.

But they cannot. Because someone else "owns" that problem.

This is the phenomenon sometimes called "cookie licking" — leaders who claim ownership of a problem space and actively prevent others from working on it, even when they lack the capacity or capability to solve it themselves. They have licked the cookie; now no one else can have it.

The result is systematic over-investment in whatever problems happen to fall within existing team boundaries — regardless of whether those are the most important problems to solve. High-priority work goes understaffed because it belongs to someone who is protecting their territory. Low-priority work gets full attention because a team exists to do it and has nowhere else to go.

This is how high-calibre people end up working on low-impact projects. Not because anyone made a bad decision, but because no one had the visibility or authority to redeploy them to where they could do more good.

The Opportunity Cost Trap

Every project requires attention, funding and bandwidth. Keeping a low-impact project alive means saying no — whether explicitly or implicitly — to something else.

The problem is that companies rarely pause to evaluate whether a project still deserves its place in the portfolio. And when they do, the comparison is usually wrong.

Most prioritisation happens within team boundaries. A team asks: "Which of our projects is most important?" This is the wrong question. The right question is: "Across the entire organisation, is this team's most important project more important than other teams' lower-priority projects?"

That question is almost never asked because the information to answer it does not exist. Leaders cannot compare work across silos when they cannot see the work in the first place.

The result: resources stay locked in place. Critical projects starve while adjacent teams have capacity to spare. Everyone is busy, but the portfolio as a whole is misaligned with what actually matters.

A Shift in Leadership Posture

Traditionally, many managers have avoided diving too deep into the details of the teams their direct reports manage. Trust your people. Do not micromanage. Give them space to run their domain.

There is wisdom in this. Managers who second-guess every decision and demand visibility into every task create dysfunction of a different kind.

But the traditional posture assumed a world of stable teams working on stable problems with relatively long time horizons. That world is changing.

Going forward, organisations will be leaner. AI will reduce headcount and increase the leverage of every person who remains. Speed and success will come from having a better, more thorough understanding of the overall portfolio and managing it more intentionally. The organisations that win will be the ones that can see reality clearly and respond to it quickly.

This requires a new posture — one where leaders maintain deeper visibility into the work being done, not to micromanage, but to spot misalignment before it compounds. Where restructuring teams is a normal part of strategy execution, not a traumatic exception. Where ending projects is treated as a leadership skill, not a failure.

This does not mean abandoning trust. It means earning trust through transparency. Teams that are confident they are working on the right things will welcome the visibility. Teams that are protecting low-value work will resist — and that resistance is information.

What Good Looks Like

An organisation that has mastered Portfolio Discipline operates differently:

Work is visible across boundaries. Leaders can see not just their direct reports' work, but the full portfolio of projects across the organisation. They know what is being worked on, by whom and why.

Regular evaluation is the norm. On a fixed cadence — monthly or quarterly — leaders review the portfolio and explicitly ask: "What should we stop?" This is not optional or ad-hoc. It is part of how the organisation operates.

Ending work is a leadership skill. Shutting down a project is treated as a sign of good judgment, not failure. Leaders who redirect resources from low-value to high-value work are recognised for it.

Teams restructure around priorities. When priorities shift, people move. This is expected and normal, not exceptional and traumatic. Employees see change as opportunity because they trust they will be given high-impact assignments.

Problem ownership is fluid. Problems belong to the organisation, not to specific teams. When a higher-priority problem emerges, the people best suited to solve it can move to it — regardless of existing org boundaries. Leaders who "cookie lick" — claiming problems they cannot adequately address — are challenged.

Leadership portfolios become fluid. When Portfolio Discipline is routine, managers stop seeing reviews as threats to their empire. Instead, they see opportunity. Yes, they might scale back an older initiative that has run its course — but they might also pick up an exciting new mandate that was previously stuck in someone else's territory. The manager who proactively identifies low-value work in their own portfolio and proposes redeployment is not sabotaging their career; they are demonstrating exactly the strategic judgment the organisation needs. Over time, the best leaders accumulate the most interesting problems — not by hoarding, but by proving they can be trusted to deploy resources where they matter most.

Ambitious people can move. Employees who see important problems they want to tackle have a path to work on them. Portfolio reviews create opportunities for people to raise their hand and be redeployed to higher-impact work. This is good for the organisation and good for retention — the best people want to work on the hardest problems.

Opportunity cost is explicit. Every prioritisation conversation includes the question: "What are we not doing because we are doing this?" Trade-offs are visible and deliberate.

The Practice

Portfolio Discipline has three components: visibility, evaluation and action.

1. Visibility

You cannot prune what you cannot see.

The first requirement is a clear, up-to-date picture of what work is being done across the organisation. This means:

- Every significant project is documented and visible

- Projects are explicitly linked to goals and metrics (see: The Alignment Stack)

- Resource allocation — who is working on what — is tracked and accessible

- Status is written, not just reported in meetings (see: The Transparency Principle)

Without this foundation, Portfolio Discipline is guesswork. Leaders will prune what is politically weak, not what is strategically low-value.

Watch for work hiding in BAU. Some of the most prunable work is not labelled as a "project" at all. It lives in Business as Usual — the ongoing operational work that keeps the organisation running. BAU is necessary, but it also accumulates. Processes that made sense five years ago persist because no one questions them. Reports that no one reads continue to be produced. Systems that were once critical become legacy burdens maintained out of habit.

Depending on how goals are structured, this work may be invisible to portfolio reviews. A team's OKRs might focus on new initiatives while 60% of their capacity goes to BAU that has never been evaluated. Effective Portfolio Discipline requires visibility into this hidden work — and the willingness to ask whether it still deserves the investment it is receiving. (See: The Alignment Stack for more on BAU and how to account for it.)

2. Evaluation

On a regular cadence, leadership teams review the portfolio with a specific mandate: identify work to stop, pause or scale down.

A critical dynamic to understand: The people closest to any project will almost always argue that the problem is not solved yet and that further investment is required. They will be right. There is always more to do. The product could be better. The system could be more robust. The customer experience could be smoother.

This is not dishonesty — it is proximity. The people doing the work see the gaps most clearly. They care about the problem they have been solving. Of course they believe it deserves continued investment.

The question is not whether further investment would create value. It almost certainly would. The question is whether that value is greater or less than what the same resources could create elsewhere. That is a question the people closest to the work are not positioned to answer — and it is why portfolio evaluation must happen at a level where the full landscape is visible.

The pruning questions:

- Would we fund this project again today? If it did not exist, would we start it now?

- Is this project still aligned with strategic priorities? Businesses evolve. Some projects that made sense six months ago may no longer be relevant.

- What is the opportunity cost? What higher-impact work is being delayed or underfunded because of this project?

- Are we iterating just because we can? Is the project still adding value, or is it continuing simply because it is already in motion?

- Does the talent match the priority? Are the right people working on this? Would they be better deployed elsewhere?

The output of the evaluation is a decision: continue, pause or end. For projects that continue, the evaluation also asks whether they are appropriately resourced — both overstaffing and understaffing are problems.

Pruning is not binary. Ending a project entirely is one option, but it is not the only one. Scaling back — reducing investment while keeping the work alive — is often the right call. A team of eight becomes a team of three. A full-time initiative becomes a part-time maintenance effort. The remaining capacity is redeployed to higher-priority work.

This matters for two reasons. First, it lowers the stakes. Leaders are more willing to act when the choice is not "keep everything or kill it entirely." Second, it makes mistakes recoverable. If you scale back a project and later realise it was more important than you thought, you can reallocate again. Portfolio Discipline is an ongoing practice, not a one-way door.

3. Action

Evaluation without action is theatre. The hard part of Portfolio Discipline is actually stopping work and moving people.

Ending a project:

- Communicate the decision with context. Explain what changed and why ending the project is the right call.

- Recognise contributions. Ending a project is not a verdict on the people who worked on it. Distinguish between "this work is no longer valuable" and "your work was not valuable."

- Preserve learnings. Capture what was learned and make it accessible. Even failed projects generate insight.

Redeploying people:

- Reassignment should be intentional, not incidental. When a project ends, the people should be placed into work that aligns with the organisation's highest priorities — not left in limbo or reassigned to low-impact maintenance work.

- Use the transition as a growth opportunity. Employees who have worked across different parts of the organisation bring invaluable perspective. Their varied experiences and cross-team connections make it easier to navigate complexity, break down silos and get things done.

The goal is to make ending projects — and reshuffling people — a normal part of how the organisation operates. Not a traumatic exception, but a routine expression of strategic focus.

Continuous Pruning, Not Periodic Upheaval

Portfolio Discipline should not feel like periodic upheaval. The goal is not dramatic reorganisations that leave people anxious about their future. The goal is small, continuous adjustments that keep the portfolio aligned with what matters most.

Think of it like the management principle that suggests evaluating the bottom 10% of performers each cycle. The same logic applies to work: each quarter, identify the bottom 10-20% of projects by strategic value. Not to eliminate them all — some will have valid reasons to continue — but to force the evaluation.

Most leaders already have a list of things they wish they could invest in. Critical initiatives that are understaffed. Opportunities they have had to pass on. Problems they know are important but cannot find capacity to address. The question is not "if we had to redeploy this capacity, where would it go?" — that framing makes it sound like a chore. The question is: "If we could redeploy this talented team to one of our critical priorities, would that be a better use of their abilities?" That framing makes it sound like what it is: an opportunity.

Why continuous beats periodic:

- Less disruption. Small changes each quarter are easier to absorb than major restructuring every few years.

- Faster course correction. Problems are caught earlier, before low-value work has consumed years of investment.

- Normalised change. When movement is routine, people stop fearing it. Redeployment becomes opportunity, not threat.

- Better information. Regular evaluation builds the muscle. Leaders get better at seeing relative value. Teams get better at articulating their impact.

The cadence matters. Monthly is too frequent for most organisations — the overhead outweighs the benefit. Annually is too slow — too much drift accumulates. Quarterly tends to be the right rhythm: frequent enough to stay responsive, infrequent enough to be meaningful.

What matters most is that it happens reliably. Portfolio Discipline is a habit, not an event.

When This Works

Portfolio Discipline is not a standalone intervention. It requires a foundation — and in organisations where that foundation is missing, it will not take root.

Start with visibility. Leaders cannot make good pruning decisions if they cannot see the work. If projects are invisible across boundaries, if status is shared only in meetings, if no one knows what adjacent teams are actually doing — Portfolio Discipline will devolve into political theatre. The loudest voices will win. The weakest sponsors will lose. Strategic value will be incidental.

This is why the Alignment Stack and Transparency Principle come first. Build the infrastructure that makes work visible. Link projects to goals and metrics. Create written status that anyone can access. Make it possible to compare work across silos. Then — and only then — does Portfolio Discipline become a strategic discipline rather than a political exercise.

Trust is built through consistent application. The first few cycles matter most. Everyone will be watching to see what happens to people whose projects are scaled back. Are they punished? Sidelined? Given low-status maintenance work? Or are they genuinely redeployed to high-value initiatives?

If early "losers" are treated poorly, the message is clear: protect your territory at all costs. If they are treated well — if scaling back a project is genuinely followed by meaningful new work — the message is different: this organisation rewards strategic thinking, not empire-building.

Leaders must also apply the process to themselves. If senior executives protect their pet projects while cutting everyone else's, trust evaporates. Portfolio Discipline only works when everyone is subject to the same evaluation.

Preconditions to assess:

- Is work visible across boundaries? Can leaders actually see what is being done outside their direct reports?

- Do leaders trust each other? Or is the leadership team a collection of competing fiefdoms?

- Is redeployment seen as opportunity or punishment? What happened to people whose projects ended in the past?

- Are incentives aligned? Does the organisation reward headcount and scope, or outcomes and judgment?

- Is there psychological safety? Can a manager admit their project is lower-value without fear of career damage?

If the answer to most of these is "no," start there. Portfolio Discipline is the capstone, not the foundation.

Portfolio Discipline and the Alignment Stack

Portfolio Discipline works hand-in-hand with The Alignment Stack.

The Alignment Stack provides the structure: metrics, goals, teams and projects in a coherent cascade. It answers the question: "What is this work supposed to achieve?"

Portfolio Discipline provides the discipline: regularly evaluating whether work still deserves its place in the stack and taking action when it does not.

An organisation with a clear Alignment Stack but no pruning practice will watch its stack become cluttered over time — projects that no longer serve active goals, teams whose mandate has drifted, metrics that no one is actually working to move.

An organisation that prunes without the Alignment Stack will cut based on politics and intuition rather than strategic alignment.

You need both.

Common Failure Modes

Pruning on gut feel

Leaders eliminate work based on political capital rather than strategic value. Projects with weak sponsors get cut; projects with powerful advocates survive regardless of merit.

Fix: Require explicit alignment to metrics and goals. Make the case for every project's continued existence visible and comparable.

Evaluation without action

Leadership teams go through the motions of reviewing the portfolio but never actually stop anything. Every project is deemed essential; nothing changes.

Fix: Set explicit targets. "This quarter we will stop or significantly scale down at least three projects." Force the trade-off.

Traumatic endings

Projects end abruptly without context or recognition. People feel their work was wasted. Trust erodes.

Fix: End projects with care. Explain the reasoning. Recognise contributions. Make clear this is about changing priorities, not inadequate performance.

Reshuffling to nowhere

Projects end, but people are dumped into low-value maintenance work or left without clear assignments. The message received: "Your work did not matter and neither do you."

Fix: Plan the redeployment before ending the project. Every person should move to work that is clearly valued.

One-time events

An organisation does a portfolio review once, makes some changes and then reverts to the old pattern of indefinite project continuation.

Fix: Make pruning a cadence, not an event. Quarterly, evaluate the bottom 10-20% of projects by strategic value. Build the muscle until it becomes routine. Small continuous adjustments are easier than periodic upheaval.

Signs Portfolio Discipline Is Working

- Leaders can articulate what the organisation has stopped investing in — not just what it is pursuing

- Ending or scaling back projects is treated as a sign of strategic discipline, not failure

- Resources move to high-priority work without political battles

- Employees trust that when their project ends, they will be given meaningful new assignments

- The organisation has fewer concurrent projects but makes faster progress on the ones that remain

- Trade-off conversations happen explicitly: "If we start this, we need to stop that"

- Teams restructure around priorities as a matter of course

- Employees who have worked across multiple areas are valued for their perspective

- Ambitious people can move to problems they want to solve

- Portfolio reviews happen on a predictable cadence — quarterly at minimum

- Small adjustments are continuous; dramatic reorganisations are rare

- The bottom 10-20% of projects by value are evaluated each cycle

- BAU work is visible and periodically reviewed, not hidden and assumed necessary

- Scaling back is used as often as ending — leaders calibrate investment, not just make binary choices

Signs Portfolio Discipline Is Broken

- Projects continue indefinitely without re-evaluation

- Everyone is busy but progress on metrics is slow

- High-calibre people are stuck on low-impact work

- Critical projects cannot find the talent they need

- Ending a project feels like admitting failure

- Reshuffling teams is treated as a disruptive exception rather than normal practice

- Leaders cannot see the full portfolio of work being done

- Prioritisation happens within team boundaries, never across them

- The organisation adds projects but never removes them

- Leaders "cookie lick" — claiming problem spaces they cannot adequately address while blocking others

- Ambitious employees cannot find a path to work on the problems they care about

- Portfolio reviews are annual events (or never) rather than continuous practice

- When change does happen, it is dramatic and traumatic

- BAU work is invisible — no one knows how much capacity it consumes or whether it is still necessary

- Decisions are all-or-nothing: projects either continue at full investment or are killed entirely

Summary

Portfolio Discipline is a model for actively managing the work an organisation is doing — and more importantly, the work it should stop doing.

Most organisations are bad at rebalancing work. Not because they lack discipline, but because the forces that perpetuate work are structural. Org structures are rigid because HR and Finance systems are built around them. Leaders cannot see the actual work being done beneath them — only layers of abstraction. Individual managers are not incentivised to give up their people. And "cookie licking" — leaders claiming problem spaces they cannot adequately address — blocks ambitious people from moving to where they could do more good.

The result is a portfolio where every project has some value, but relative priorities have drifted. Teams that were stood up three years ago are still optimising within their scope while the landscape has shifted around them. The work is not worthless — it is just a tenth as valuable as something else those people could be doing.

Portfolio Discipline addresses this through three practices: visibility (knowing what work is being done across the organisation), evaluation (regularly asking what should stop) and action (actually ending projects and redeploying people to higher-value work).

Two principles make this work:

Portfolio management is a team sport. Individual managers will never voluntarily give up their people — it feels like career sabotage. The only way rebalancing happens is when leadership teams are transparent about their investments and make trade-off decisions together.

Continuous pruning beats periodic upheaval. The goal is not dramatic reorganisations that leave people anxious. The goal is small, steady adjustments — evaluating the bottom 10-20% of projects by value each quarter, building the habit of asking "what should we stop?" until it becomes normal. When change is routine, people stop fearing it.

Pruning is not binary. Scaling back is often the right call — reducing investment while keeping work alive. This lowers the stakes and makes mistakes recoverable. If you scale back too far, you can reallocate again.

Most leaders already have a list of critical priorities they wish they could staff. Portfolio Discipline is how they find the capacity. The question is not "if we had to redeploy these people, where would they go?" — that sounds like a chore. The question is "if we could redeploy this talented team to a critical priority, would that be better?" That sounds like what it is: an opportunity.

The people closest to any project will always argue that more investment is needed — and they will be right. There is always more to do. The question is not whether further investment would create value, but whether it would create more value than the same resources deployed elsewhere. That is a question only visible at the portfolio level.

Ending a project is not failure. It is the sign of an organisation that knows how to prioritise — and that has built the muscle to do so continuously.

Want to bring clarity to your organization?

See how Clarity Forge can help transform your team.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.