The Transparency Principle

A Clarity Framework for making sure people have the information they need.

Purpose

The Transparency Principle is a model for ensuring people have access to — and can actually use — the information they need to be effective.

This is harder than it sounds. Access is necessary but not sufficient. A goal buried in a 40-page strategy document is technically accessible. A project update shared verbally in a meeting and never written down is technically shared. Neither helps the person who needs context at 3pm on a Tuesday when they are trying to make a decision.

The Transparency Principle addresses both problems: the information that is hidden and the information that is nominally available but practically unusable. It provides a framework for diagnosing where transparency breaks down, making the case for change and defining what effective transparency actually looks like.

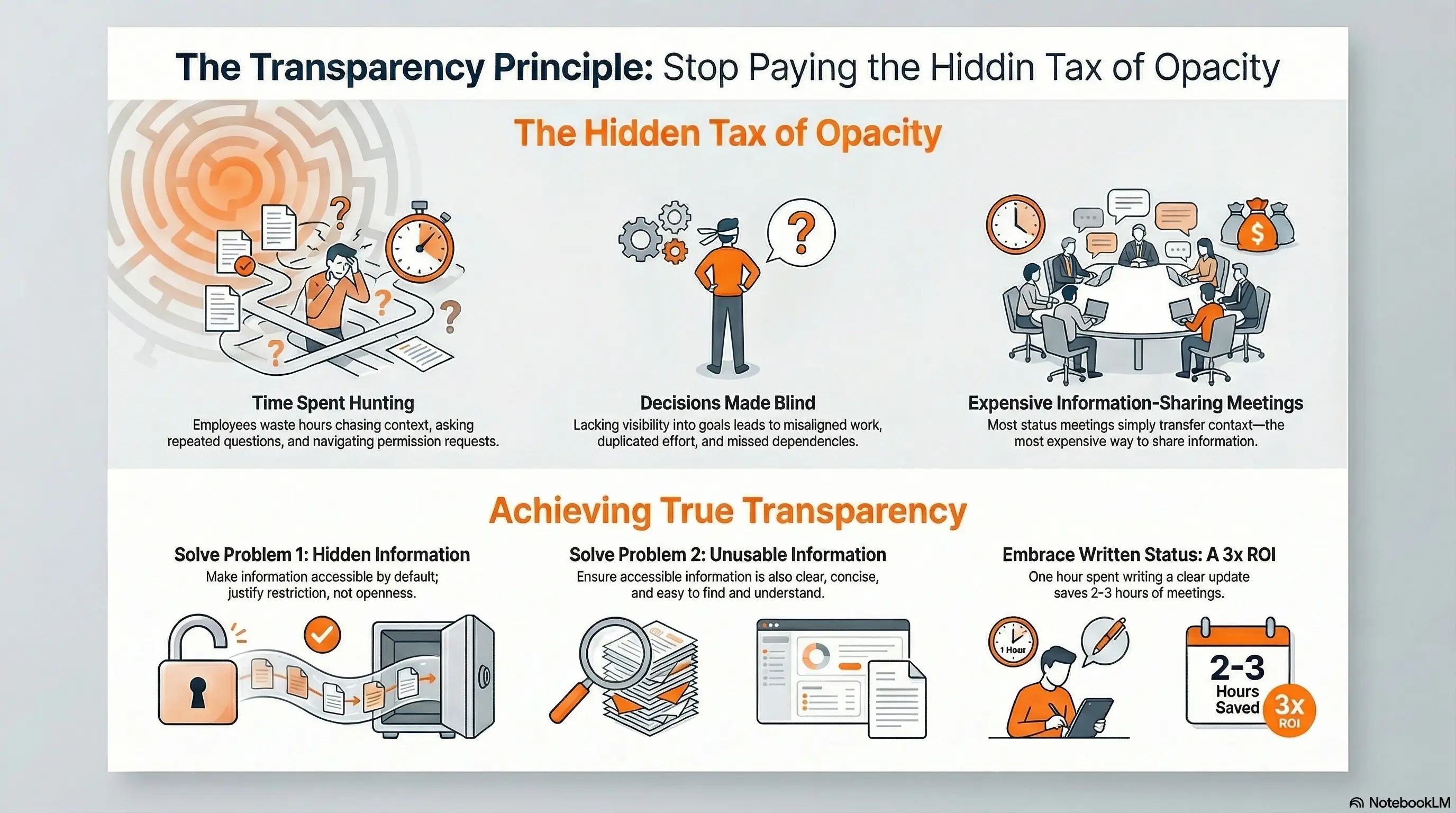

The Real Cost of Opacity

Every organisation pays a tax on missing and inaccessible information. The tax is never itemised, but it shows up everywhere.

Time spent hunting. Employees chase context. They ask questions in chat that have been answered before. They schedule meetings to learn things that should be written down. They navigate folder structures and permission requests and "ask Sarah, she might know."

Decisions made partly blind. When people lack visibility into goals, priorities and what others are working on, they guess. Sometimes they guess well. Often they do not. The cost of a wrong guess — misaligned work, duplicated effort, missed dependencies — is rarely attributed to the information gap that caused it.

Meetings that exist to distribute information. A remarkable number of meetings exist not for discussion or decision-making but simply to transfer context from one person to others. This is the most expensive possible way to share information. It requires synchronous attendance. It produces no artifact. It is not discoverable by anyone who was not in the room.

Disengagement. When employees cannot see how their work connects to the broader picture, many stop trying to connect it. They do what they are told. They wait for direction. The discretionary effort that comes from understanding and caring about outcomes disappears.

The tax is real. Most organisations have no idea how much they are paying.

Two Transparency Problems

Transparency fails in two distinct ways. Solving only one leaves the other intact.

Problem 1: Information That Is Hidden

This is the obvious failure. Documents are locked in private folders. Channels default to private. Meetings are marked confidential when there is nothing confidential about them. Information is shared on a need-to-know basis, with the working assumption that most people do not need to know.

The causes vary:

- Habit. The default settings favour privacy and no one changes them.

- Fear of accountability. Invisible work cannot be scrutinised.

- Information as leverage. Some people believe that controlling access gives them influence.

- Perfectionism. Leaders wait until work is polished before sharing it, depriving others of context for weeks or months.

- Overblown security concerns. The fear of leaks applied to information that has no competitive value.

Hidden information is a solvable problem. Change the defaults. Open the folders. Make channels public unless there is a reason not to.

But this only solves half the problem.

Problem 2: Information That Is Unusable

Information can be technically accessible and practically useless.

Goals buried in dense documents. The strategy exists. It is 47 pages long. It is written for the executive team, full of acronyms and references that require context the reader does not have. By page 12, most people have given up. The goal is "accessible" in the sense that the document is shared. It is not accessible in the sense that anyone can find, understand and use it.

Status shared only in meetings. A project gets five minutes in a weekly review. The team explains what they are working on, what is blocked and what is coming next. This information is shared — to the people in the room, at that moment. It is not written down. It is not discoverable. It does not exist for the person who joins the project next month or the adjacent team that would have benefited from knowing.

Scattered and inconsistent formats. One team tracks work in Jira. Another uses Notion. A third relies on a shared spreadsheet that no one updates. Even if all of these are "accessible," finding information requires knowing where to look, which requires knowing who to ask, which defeats the purpose.

Jargon and assumed context. Information written for insiders is opaque to everyone else. Acronyms unexplained. Dependencies unnamed. History assumed. The reader cannot evaluate what they are reading because they lack the background to understand it.

Transparency that solves only the access problem produces organisations where information is technically available and practically unfindable. The Transparency Principle addresses both.

The Hidden Demand for Context

One reason leaders underinvest in transparency is that they do not see the demand.

Leaders occupy a privileged position in the information flow. Context comes to them. They sit in the meetings where decisions are made. They receive the updates. They are copied on the emails. The work of hunting for information — the permission requests, the "do you know who I should ask about X?" messages, the meetings scheduled just to get context — is largely invisible to them because they rarely have to do it.

This creates a blind spot. Leaders underestimate how much time others spend hunting because they do not experience the hunt themselves.

There is a pattern worth noticing: people discover projects through the grapevine. They hear about something in a hallway conversation or a passing mention in a meeting. They realise it is relevant to their work and they want to know more. They reach out.

These are the visible cases — the connections that happened despite the opacity. But for every person who reaches out, there are others who would have if they had known. The executive who would have flagged a risk had they seen the status report. The PM who would have caught the dependency issue before it became a crisis. The architect who would have pointed out that another team solved this problem last year.

And then there are the failures that no one ever connects to transparency at all. The competing project that was spun up, staffed and ran for three years. The strategic initiative that failed because a critical insight sat in a document no one outside the original team ever saw. The talent that left because they could not see how their work connected to anything that mattered.

This is the hidden demand. It is invisible because it only surfaces when information happens to travel through informal channels. The people who never stumbled onto the relevant context never knew to ask. Their need was real, but it was never expressed. The costs were real, but they were never attributed to the information gap that caused them.

Transparency creates the conditions for serendipitous discovery. It allows people to find what they did not know to look for. It connects work that would otherwise proceed in isolation.

You cannot see this demand until you create the supply.

The Case for Written Status

Many organisations resist written status updates. They feel like overhead. Another document no one reads. Bureaucracy for bureaucracy's sake.

This intuition is backwards.

Consider what happens without written status. A project lead attends a weekly meeting. They spend five minutes summarising where things stand. They answer questions. The information is transferred — to the people in the room, at that moment.

Now consider the cost:

- The meeting requires synchronous attendance from everyone who might benefit from the information.

- The information is gone as soon as the meeting ends. It is not discoverable. It cannot be referenced. It does not exist for anyone who was not present.

- The project lead will repeat substantially the same update in their next 1:1, in a stakeholder check-in, in an email thread when someone asks. The same information, transferred multiple times, because it was never written down.

For every hour someone spends writing a status update — a well-structured summary of progress, blockers and next steps — they are likely saving two or three hours of meetings and ad-hoc explanations. The written version is permanent. It is discoverable. It can be consumed asynchronously by anyone who needs it, whenever they need it.

The thinking benefit. There is a second payoff that has nothing to do with communication: the discipline of writing clarifies thinking. This is the principle behind Amazon's famous requirement to write a six-page memo before holding a meeting. Bezos understood that forcing people to write — in complete sentences, with logical structure — surfaces fuzzy thinking that slides past in conversation. The author discovers gaps in their reasoning. They identify problems they would otherwise have glossed over. The act of writing is itself valuable, separate from anything that happens after.

Status updates work the same way. Articulating progress, blockers and next steps in prose forces the author to organise their thoughts. "We're making good progress" becomes "We completed X and Y; Z is blocked waiting on the API team; we expect to finish by Thursday if the dependency resolves." The second version is useful. The first is not.

Status updates feel like overhead because the cost is visible and the benefit is diffuse. But the ROI is real. Organisations that invest in written status reporting spend less time in meetings, make information discoverable and develop a record of execution that can be referenced when questions arise months later.

The Transparency Audit

Before you can improve transparency, you need to see where it is broken. The Transparency Audit diagnoses gaps in goals and execution — the two areas where opacity creates the most friction.

Goal Transparency

The question: Can people find, understand and use the goals and priorities that should guide their work?

What to look for:

- Are goals documented in a format that is consumable — clear, concise and free of insider jargon?

- Can employees find current priorities without navigating dense strategy documents or asking someone who knows?

- Is the reasoning behind goals accessible, or only the goals themselves?

- When priorities change, does the change reach everyone it affects?

Red flags:

- Goals exist but are buried in long documents that few people read

- Employees can name company priorities but cannot explain why they matter or how they connect to their work

- Strategic updates happen in meetings that most affected people do not attend

- Acronyms and jargon make goal documents unreadable to anyone outside the inner circle

Execution Transparency

The question: Can people see what is being worked on, what is blocked and how projects are progressing — without having to ask?

What to look for:

- Is project status written down, or only shared verbally in meetings?

- Can someone outside the immediate team understand the state of a project without scheduling a call?

- Are dependencies between teams visible before they become problems?

- Is there a consistent format for status that makes information discoverable across teams?

Red flags:

- Status is shared in meetings but not documented

- The only way to learn what a team is working on is to ask someone on that team

- Dependencies surface as surprises rather than planned handoffs

- People spend significant time in meetings that exist primarily to transfer information

The Transparency Spectrum

Not all information should be fully public. The goal is not maximum transparency everywhere but deliberate positioning rather than default opacity.

| Level | Description | When Appropriate |

|---|---|---|

| Restricted | Access limited to specific individuals | Sensitive personnel matters, legal exposure, genuine trade secrets |

| Need-to-know | Shared with those who have a defined need | Confidential negotiations, pre-announcement plans |

| Team-visible | Shared within a team or department | Early work-in-progress not ready for broader input |

| Broadly accessible | Available to anyone who looks | Goals, project status, decisions, documentation |

| Proactively shared | Actively pushed to those who should see it | Critical updates, changes that affect others, blockers |

Most organisations default to "need-to-know" when they should default to "broadly accessible." The Transparency Principle asks you to justify restriction rather than justify openness.

The test: For any piece of information, ask: "Who might need this later that I have not thought of?" If the answer is not "no one," make it accessible now.

What Transparency Looks Like in Practice

Goals

- Goals are documented in a format that can be consumed in minutes, not hours

- The reasoning behind goals — why these and not others — is explained

- Progress is updated regularly and visible without asking

- Acronyms are spelled out; context is provided for readers outside the inner circle

- Anyone can trace their work to the goals it serves

Execution

- Status is written down, not just shared verbally

- Updates follow a consistent format that makes information discoverable across teams

- Blockers are documented and visible to anyone who might help

- Dependencies are tracked explicitly, not discovered when something breaks

- Documentation is maintained and searchable

Decisions

- Key decisions are recorded with their rationale

- The record is accessible to anyone affected, not just those in the room

- When decisions change, the change and the reasoning are communicated

Tools and Defaults

- Channels and folders default to accessible unless there is a reason for restriction

- A shared knowledge base exists and is maintained

- Information architecture makes things findable, not just technically available

The right tooling makes transparency dramatically easier. Clarity Forge, for example, is designed around these principles: goals captured in a consistent format across teams, dependencies between teams tracked explicitly, status reports surfaced to people affected by risk, not because someone remembered to share, but because the system connects the dots.

The Transparency Principle can be practiced with any tools, but tools built for discoverability reduce the friction that causes organisations to drift back toward opacity.

Making the Case

Changing transparency defaults requires buy-in. Here is how to build the case.

Quantify the cost of opacity

- How many hours per week do people spend in meetings that exist primarily to share information?

- How often are questions repeated in chat because answers are not documented?

- How frequently is work duplicated because teams did not know what others were building?

- How much time is lost to permission requests and information hunting?

Even rough estimates can be compelling. "We estimate our team spends 6-8 hours per week in status meetings that could be replaced by written updates" is a concrete cost.

Highlight the hidden demand

- Track instances where people discovered relevant work through the grapevine

- Note when someone said "I wish I had known about this sooner"

- Surface the connections that almost did not happen

Reframe the ROI of written status

- One hour writing saves two to three hours of meetings

- Written status is permanent, discoverable and asynchronous

- The discipline of writing clarifies thinking — this is the Bezos memo principle applied to execution

- Status meetings become discussion, not information transfer

Address the objections

"Sharing early is risky." Share the plan and the conditions under which it might change. Employees can handle uncertainty. What they cannot handle is being blindsided.

"No one will read it." Some will not. But for those who need it, the information will be there. And you will stop repeating the same updates in multiple forums.

"People will be distracted by too much information." They will not scroll corporate documents for entertainment. They will access what they need and ignore the rest. What distracts them now is hunting for information they cannot find.

Signs the Transparency Principle Is Working

- Employees can answer "What are we trying to achieve?" without asking anyone

- New hires orient themselves quickly because information is findable

- Status meetings focus on discussion, not information transfer

- Teams take dependencies on each other because they can see what others are working on

- People discover relevant work they did not know to look for

- Decisions include documentation of rationale

- The same questions stop being asked repeatedly

- Written status updates reduce meeting load

- Information hunting decreases noticeably

Signs the Transparency Principle Is Broken

- Employees attend meetings primarily to gather information they cannot access otherwise

- The same questions appear repeatedly in chat

- Status is shared verbally but not written down

- Goals exist but are buried in documents no one reads

- Teams duplicate work because they did not know someone else was building it

- Decisions are announced without explanation

- New hires take months to find their footing

- "Ask Sarah" is the answer to too many questions

- People complain about too many meetings while resisting the written updates that would replace them

Summary

The Transparency Principle is a model for ensuring people have access to — and can actually use — the information they need to be effective.

Transparency fails in two ways. The first is hidden information: documents locked away, channels defaulting to private, sharing on a need-to-know basis. The second is unusable information: goals buried in dense documents, status shared only in meetings, context scattered across inconsistent formats. Solving only one leaves the other intact.

Leaders often underestimate the problem because they occupy a privileged position in the information flow. Context comes to them. They do not experience the hunt that others endure daily.

The demand for transparency is often hidden. People discover relevant work through the grapevine and wish they had known sooner. For every person who reaches out, there is someone who would have — if they had known the work existed. You cannot see this demand until you create the supply.

Written status has a higher ROI than it appears. For every hour spent writing, two or three are saved in meetings and repeated explanations. The written version is permanent, discoverable and asynchronous. And like Amazon's six-page memo requirement, the discipline of writing clarifies thinking — surfacing gaps and forcing rigour that conversation allows to slide past.

The Transparency Audit diagnoses where access and usability are broken. The Transparency Spectrum helps position information deliberately. The goal is not maximum transparency everywhere but conscious choices about what should be accessible and in what form.

Transparency is key to clarity. Organisations that embrace effective transparency spend less time hunting, hold fewer meetings and make better decisions. The information people need exists, they can find it and they can use it. That is the principle.

Want to bring clarity to your organization?

See how Clarity Forge can help transform your team.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.