The Refinement Principle

Maintaining clarity through continuous adjustment, not periodic overhaul.

Purpose

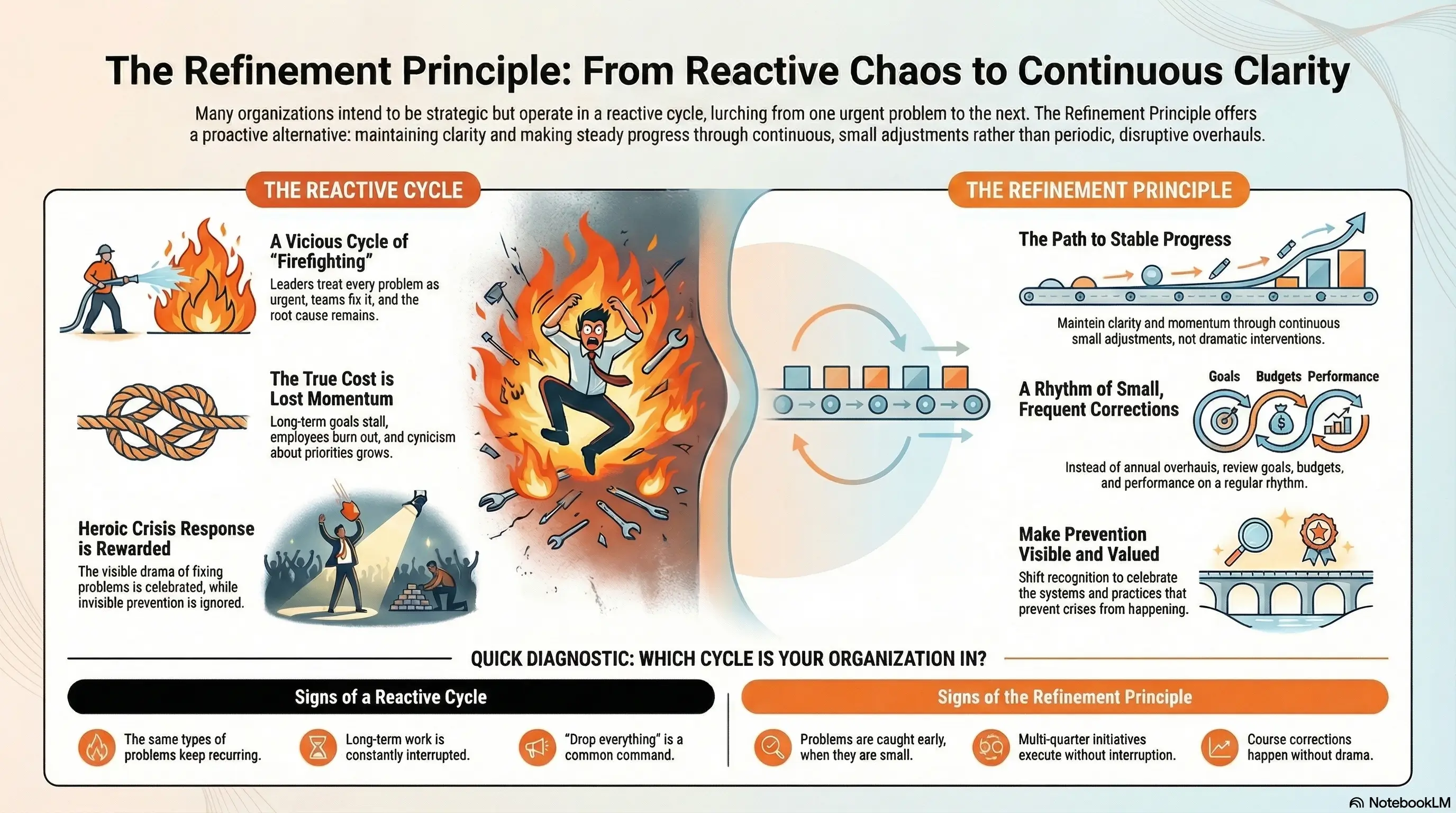

Ask a leader how their organisation operates and they will describe strategy, planning, execution. Watch the same organisation for a month and you will see something different: a pattern of lurching from one urgent problem to the next.

This gap between intention and reality is common. Organisations have goals and plans, but the daily experience is reactive, responding to whatever feels most pressing, redirecting resources to address the latest alarm, celebrating the people who dropped everything to solve an unexpected problem.

The pattern feels productive. Urgent work gets done and problems get solved, but something important is lost: the ability to make steady progress on things that matter. Long-term initiatives stall because short-term demands keep interrupting. The same types of problems recur because no one has time to address root causes. Employees become cynical about stated priorities because those priorities get abandoned whenever something urgent appears.

The underlying issue is not that crises happen. It is that the organisation lacks the operating rhythm to prevent them, or to absorb them without disruption when they do occur.

The Refinement Principle offers a different approach: maintain clarity through continuous small adjustments rather than periodic overhauls. An organisation that refines constantly - adjusting goals as context changes, addressing small problems before they become large ones, keeping priorities current through regular review - rarely needs to declare emergencies. When something unexpected does happen, the response fits within the normal rhythm rather than derailing it.

This is what separates organisations that thrive from those that merely survive. The difference is not better crisis response. It is fewer crises worth responding to.

The Reactive Cycle

There is a pattern that looks like strong leadership but is actually the opposite.

A problem surfaces. Leaders treat it as urgent, redirecting attention and resources. Teams mobilise. The immediate issue gets resolved. Everyone returns to normal, until the next problem surfaces and the cycle repeats.

Each iteration feels like success. The organisation responded and the problem was solved, but zoom out and the picture changes. The same categories of problems keep appearing. Strategic initiatives never reach completion because they keep getting interrupted. The people who get recognised are not the ones building durable systems, they are the ones who respond fastest when things break.

Why the cycle persists:

No one stops to ask why the problem occurred. The focus is entirely on resolution, not prevention. Once the immediate pressure lifts, attention moves elsewhere. The conditions that created the problem remain unchanged, so similar problems continue to emerge.

Over time, this becomes self-reinforcing. Employees learn that reacting to emergencies is how you get noticed. Planning loses credibility because plans keep getting abandoned. The organisation develops a kind of learned helplessness about its own priorities, everyone knows that stated goals can be overridden at any moment.

The real cost:

Organisations stuck in this cycle cannot build momentum. They cannot execute anything that requires sustained focus over multiple quarters. They burn through the energy of their best people and they create a culture of cynicism where no one believes that today's priority will still matter next week.

The cycle is not caused by external forces, it is caused by missing habits. The regular practices that would catch problems early, keep priorities current and maintain alignment without drama.

Problems as Diagnostic Signals

When something goes wrong, the instinct is to fix it. But the more useful question is: why did we not see this coming?

Every significant problem that catches an organisation off guard points to a gap in its operating rhythm. The problem itself is just the visible symptom. The underlying issue is a missing practice that would have surfaced the problem earlier, or prevented it entirely.

Financial surprise. Leadership announces an urgent cost-cutting initiative. Projects are cancelled and hiring is frozen. But costs do not spiral overnight. They drift upward over months while no one is watching. The gap: regular financial review with real accountability, where small adjustments happen continuously instead of dramatic corrections happening too late.

Quality failure. A major customer escalates. Engineers are pulled from planned work. An emergency initiative launches. But quality does not collapse suddenly. Defects accumulate while no one tracks them. The gap: continuous quality monitoring, where issues are caught and addressed before they compound.

Engagement collapse. Survey scores plummet. Leadership scrambles for quick fixes. But engagement does not evaporate overnight. It erodes gradually through accumulated frustrations and unaddressed concerns. The gap: ongoing attention to how people are actually doing, not just annual measurement.

In each case, the dramatic intervention would have been unnecessary if a simpler habit had been in place. The crisis is a signal. The question is whether the organisation treats it as one.

When Disruption Is the Point

In January 2002, Bill Gates declared security Microsoft's top priority. What followed was unprecedented: the company stopped all product development for a month. Thousands of engineers reviewed code for vulnerabilities, attended security training and rebuilt their understanding of secure development.

This was not firefighting. It was intentional disruption designed to establish a new habit.

Microsoft's security problems had accumulated over years. Windows was notoriously vulnerable. The culture of shipping features fast had consistently deprioritised security. Incremental fixes were not going to work, the organisation needed a reset.

The stand-down made a point that no memo could: security now mattered more than shipping, and it worked. Security reviews became standard. The dramatic intervention created habits that persisted.

The distinction matters:

-

Firefighting: "We have a security breach, drop everything and fix it." The crisis passes, nothing changes, the next breach triggers the same response.

-

Intentional disruption: "Our security culture is broken, we are stopping everything to rebuild it." A deliberate choice to use a dramatic moment to change how the organisation operates.

Sometimes disruption is necessary, but it should be the exception. An organisation that needs dramatic interventions frequently has not built the habits those interventions were supposed to create.

The test: after the disruption, did a new habit emerge? If Microsoft had done their stand-down and gone back to the old ways, it would have been expensive firefighting. Because they used it to establish lasting practices, it was a strategic reset.

Small Corrections, Not Dramatic Pivots

The best-run organisations do not make large, disruptive changes. They make small, continuous ones.

This is the Refinement Principle in practice: instead of letting problems accumulate until they require emergency intervention, address them incrementally as part of regular operations. Instead of overhauling strategy annually, refine it continuously so it stays current.

The OKR example:

Many organisations treat OKRs as an annual or semi-annual exercise. Teams spend weeks writing fresh objectives, negotiating targets, aligning across departments. Then the OKRs are set and often carved in stone until the next planning cycle.

This is backwards. OKRs should be refined regularly, not rewritten periodically. Keep objectives that are still relevant, update ones where context has changed, drop ones that no longer matter and add new ones when necessary.

One common objection is "we cannot refine OKRs frequently, every change requires too much coordination." This objection usually reveals a process problem, not a coordination problem. If OKR adjustments require layers of approval, review committees and weeks of negotiation, the process is too heavy. Streamline it. Most refinements need only a conversation with directly affected teams and an update to documented goals.

Another common objection is "we use OKRs to create accountability for our performance review cycles". However, as we argue in the Contribution Clarity model, performance should be based on the objective impact employees make, not their adherence to a plan written 6-12 months ago.

Here is what a light-touch rhythm might look like:

- Weekly or biweekly: Teams review progress. Are we on track? Does anything need adjustment?

- Monthly: Leaders review across teams. Are priorities still aligned? Do any objectives need updating?

- Quarterly: Step back and assess. Which OKRs are complete or no longer relevant? What new objectives should be added?

This keeps goals current without the overhead of comprehensive rewrites. The cost of not refining - stale targets, drifting priorities, work that no longer matters - is far higher than the cost of light-touch adjustments.

The same principle applies everywhere:

- Portfolio management: Do not wait for an annual planning cycle to stop low-value work. Review the portfolio regularly and prune continuously.

- Performance conversations: Do not save feedback for annual reviews. Calibrate continuously so there are no surprises.

- Strategic alignment: Do not assume the Alignment Stack stays valid for a year. Revisit it quarterly to ensure work still maps to goals.

- Financial management: Do not review budgets annually and then react to overruns. Track continuously and adjust incrementally.

In each case, the principle is the same: small corrections frequently, rather than large corrections rarely. Problems stay small. Priorities stay current. The organisation maintains clarity without dramatic interventions.

Recognition Shapes Behaviour

What gets celebrated becomes what people optimise for.

When the all-hands meeting highlights the team that worked through the weekend to resolve an outage, the message is clear: heroic response is valued. In and of itself, there is nothing wrong with that, but when the person who quietly built the monitoring system that prevented three potential outages goes unmentioned, the message is equally clear: prevention is invisible.

This is how reactive cultures sustain themselves. The visible drama of crisis response earns recognition. The invisible work of crisis prevention earns nothing. Rational employees draw the obvious conclusion about where to invest their energy.

Shifting recognition:

- Celebrate the absence of problems, not just their resolution

- Highlight the systems and practices that keep things running smoothly

- Ask, when heroics occur, what made them necessary and whether that can be prevented

- Make prevention visible by naming the crises that did not happen

Leaders set the tone:

What leaders pay attention to signals what matters. A leader who frequently expresses alarm - about costs, about competitors, about customer issues - trains the organisation to be reactive. Every concern becomes potential urgency.

The alternative is to channel concerns through the regular rhythm. "This needs attention, let us add it to our monthly review" sends a different signal than "This is a problem, we need to address it now." Both take the issue seriously, but only one reinforces the habit of continuous refinement over reactive scrambling.

The Practices That Prevent Reactive Cycles

The Clarity Frameworks each embed specific practices that reduce the need for dramatic interventions:

Strategic clarity: Regular review of whether goals and metrics remain the right targets. Continuous assessment of whether work in the portfolio is still aligned. Periodic check-ins on whether strategic context has shifted.

Execution clarity: Regular status reviews with genuine accountability. Early warning systems that surface risks before they become blockers. Ongoing scope management to ensure effort stays focused on what matters.

Talent clarity: Continuous calibration conversations so contributions are understood in real time. Regular development discussions so growth stays on track. Ongoing feedback so performance reviews hold no surprises.

Culture clarity: Regular attention to team health and morale. Ongoing reinforcement of desired behaviours. Continuous monitoring of whether norms match espoused values.

None of these practices are dramatic. None create urgency. That is precisely the point — they prevent urgency by catching issues early and keeping alignment current.

An organisation with strong practices rarely needs to redirect resources or declare emergencies. When something unexpected does occur, it treats the event as a diagnostic signal and asks what practice needs to be added or strengthened.

Signs the Refinement Principle Is Working

- Problems surface early, when they are still small

- Goals and priorities evolve incrementally rather than being overhauled periodically

- Course corrections happen without drama

- Employees trust that stated priorities will remain stable

- Multi-quarter initiatives can be executed without constant interruption

- Prevention is visible and recognised, not just crisis response

- "Drop everything" is rare, most adjustments fit within the normal rhythm

- When intentional disruption does occur, it establishes lasting practices

Signs the Refinement Principle Is Broken

- The same categories of problems keep recurring

- Leadership frequently redirects resources to address urgent issues

- Dramatic interventions happen but the underlying patterns persist

- Heroic crisis response is celebrated; prevention goes unrecognised

- Long-term work is constantly interrupted by short-term demands

- Goals are set periodically and then ignored until the next cycle

- Employees are cynical about stated priorities

- Leaders frequently express alarm, triggering reactive scrambles

- When problems occur, no one asks what practice would have prevented them

Summary

The Refinement Principle is simple: maintain clarity through continuous small adjustments rather than periodic overhauls.

Organisations that operate reactively, lurching from one urgent problem to the next, feel productive but are actually fragile. They cannot sustain focus on long-term initiatives. They burn out their best people. They create cynicism about stated priorities and they keep encountering the same types of problems because no one addresses root causes.

The alternative is a rhythm of continuous refinement. Goals reviewed and adjusted regularly, not rewritten annually. Problems addressed when small, not after they become crises. Priorities kept current through ongoing attention, not defended until the next planning cycle.

Sometimes intentional disruption is necessary - Microsoft stopping development for a month to rebuild their security culture is an example - but such interventions should be rare and strategic, designed to establish new habits. If dramatic resets happen frequently, the organisation has not built the disciplines those resets were supposed to create.

What leaders recognise shapes what employees optimise for. If heroic crisis response is celebrated and steady prevention is invisible, the organisation will produce more crises to respond to. Changing this requires making prevention visible and channelling concerns through the regular operating rhythm rather than treating them as emergencies.

Clarity is not achieved once. It is maintained through the accumulation of small, consistent practices - the habits that catch problems early, keep priorities current and allow the organisation to absorb unexpected events without derailing.

Is your organisation built on habits or heroics?

Clarity Forge builds refinement into your operating rhythm — so problems stay small and priorities stay current.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.