Articulating Excellence

Describing what good looks like so you can hire for it, develop toward it and reward it.

Purpose

Every leadership team has a vision of the workforce they wish they had.

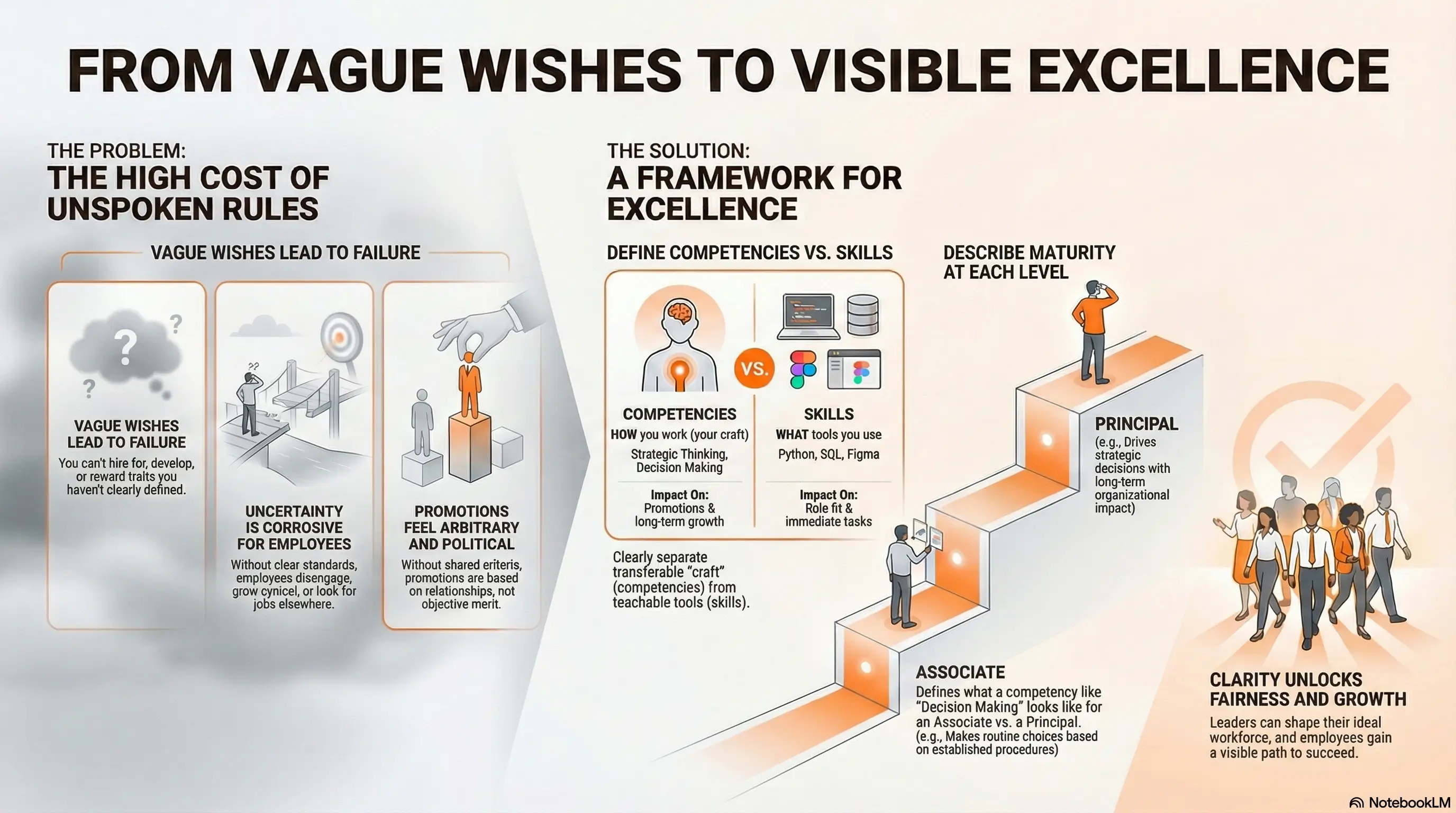

"We need more people who can think strategically." "We need people who take initiative." "We need better decision makers." These wishes surface in executive meetings, in hiring debriefs, in frustrated post-mortems after projects go sideways. Leaders know what they want. They just have not written it down.

This is a remarkable failure. If you want a workforce that thinks strategically, you must define what strategic thinking looks like — at each level, in observable terms. If you want people who take initiative, you must describe what initiative means for an associate versus a principal. If you want better decision makers, you must articulate the difference between good and great decision making in your context.

Until you do this work, your wishes remain wishes. You cannot hire for competencies you have not defined. You cannot develop people toward standards you have not articulated. You cannot reward behaviours you cannot describe. You are left hoping the right people show up and figure it out — and complaining when they do not.

The failure cascades to employees. They show up, work hard and wait to find out how they are perceived. When reviews come, some are surprised — they thought they were doing well but the rating says otherwise. Others are frustrated — they have been told to "improve communication" for three cycles without ever learning what that actually means. The ambitious ones ask directly: "What do I need to do to get promoted?" Too often, the answer is vague or different depending on who they ask.

This uncertainty is corrosive. Employees who do not understand the rules disengage. They stop investing discretionary effort because the payoff feels arbitrary. They start looking for jobs at companies where the path seems clearer. Or they stay but grow cynical, telling new hires that success here is about politics, not performance.

The damage compounds in calibration. Managers advocate for their people, but without shared standards, advocacy becomes a contest of confidence and relationships. The manager who "plays the game" gets their people promoted. The manager who assumes merit will speak for itself watches their best performers get passed over. Word spreads. Fairness erodes. The same questions surface in every town hall: "How do I know what's expected of me? Why did that person get promoted and not me?"

Articulating Excellence solves both problems. It forces leaders to define what excellence looks like — transforming vague wishes into concrete definitions that can be hired for, developed toward and rewarded. And it makes the rules visible to employees, so they know how to succeed and can trust that evaluation is fair.

The work is not trivial. But the cost of not doing it — paid in a workforce that never becomes what you need, and a culture that drives away the people who could get you there — is far higher.

Competencies vs Skills

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same thing. The distinction matters.

Competencies are transferable capabilities that define how good someone is at the craft of their role. Decision making. Stakeholder management. Communication. Strategic thinking. Technical judgment. These travel with you across teams, companies and even industries. They are hard to develop and take years to master. They should drive performance and promotion decisions.

Skills are specific technical abilities that enable execution in a particular context. Python. SQL. Figma. A particular framework or methodology. A specific domain expertise. These matter for role fit, but they are more teachable and more local — what skills matter depends heavily on the team and the work.

The distinction helps organisations make better decisions:

A great product manager with weak SQL skills can learn SQL. A product manager with strong SQL skills but weak stakeholder management has a harder problem. When evaluating someone for promotion, competencies should carry more weight than skills. When evaluating someone for a specific role, skills might determine fit even if competencies are strong.

Competencies answer: How good is this person at the craft of their role?

Skills answer: Can this person use the specific tools we need right now?

Both matter. But conflating them leads to confusion — promoting someone because they have impressive technical skills while ignoring competency gaps, or blocking someone's growth because they lack a skill that could be taught in a month.

Defining Competencies

A competency is a behaviour, capability or judgment that employees need to succeed in their role. Good competency definitions share a few qualities:

Observable. You should be able to point to specific behaviours or outcomes that demonstrate the competency. "Strategic thinking" is vague. "Identifies opportunities and threats that others miss, and shapes plans that account for them" is observable.

Distinct from each other. If two competencies overlap heavily, combine them or sharpen the distinction. You want a manageable set of competencies across the organisation — not an exhaustive inventory that no one can remember.

Stable over time. Competencies should not change quarter to quarter. They represent the enduring capabilities that define excellence. Skills change as technology and context evolve; competencies should be more durable.

Shared definitions, custom application. "Decision making" should mean the same thing whether you are evaluating a product manager or an engineer. Maintaining separate definitions for each role creates unnecessary complexity and makes cross-functional comparison impossible. However, which competencies matter for each role should be customised. A product manager needs strong stakeholder management; an engineer needs strong technical judgment. The definition of stakeholder management is universal — whether it applies to a given role is configurable.

Maturity Descriptions

Abstract ratings do not work. If you ask ten managers what "3 out of 5" means for decision making, you will get ten different answers. Ratings cluster in the middle because no one can justify the extremes. The framework becomes a formality rather than a tool.

The solution is to define what each competency looks like at each level band — associate, senior, principal, or whatever levels your organisation uses. Then you rate someone by asking which level description best fits what you observe.

Example: Decision Making

Associate level: Makes sound decisions within their area of ownership. Recognises when to escalate. Seeks input appropriately before committing.

Senior level: Makes complex decisions that span team boundaries. Weighs competing stakeholder interests. Comfortable with ambiguity in their domain. Accepts accountability for outcomes.

Principal level: Makes organisation-level decisions with incomplete information. Navigates political complexity. Helps others develop decision-making judgment. Owns decisions that set precedent.

Now evaluation becomes concrete. You sit down with a senior-level employee and ask: "Does your decision making look more like the senior description or the principal description?" If they consistently demonstrate principal-level decision making, you rate them as principal level in that competency — even though their job title is senior.

This approach makes growth visible. A senior employee rated at senior level across all competencies knows they are meeting expectations. A senior employee rated at principal level in three competencies and senior level in two can see exactly where the growth opportunity lies. And a senior employee ready for promotion has evidence: "I am already operating at principal level in every competency that matters for this role."

Aggregation works naturally. You can see how many employees are rated at each level for each competency. You can identify organisational gaps — perhaps no one in the team is operating at principal level in stakeholder management. You can track development over time without abstract numbers that mean different things to different people.

The Hard Work of Writing Descriptions

This is where most organisations fail. Writing competency descriptions that are specific enough to be useful, general enough to apply broadly and clear enough that different managers interpret them consistently — this is genuinely difficult work.

A few principles help:

Use concrete language. Avoid words like "effectively," "appropriately," or "demonstrates strong." These mean different things to different people. Instead, describe specific behaviours or outcomes. "Identifies risks before they become problems" is better than "manages risk effectively."

Describe the difference between levels. The value of the framework is in distinguishing between levels. If your senior and principal descriptions sound similar, you have not done the hard work of articulating what changes as someone grows. Focus on scope, complexity, ambiguity and influence.

Test with real examples. Take actual employees and try to place them using your descriptions. If the descriptions do not clearly differentiate people you know are at different levels, revise them. If managers disagree on placement, the descriptions are not specific enough.

Expect iteration. You will not get this right on the first pass. Publish a draft, use it for a cycle, gather feedback and refine. The descriptions will improve as managers apply them and discover where they break down.

Get alignment before publishing. The process of writing descriptions forces leaders to articulate what they actually value. Disagreements will surface — one leader thinks strategic thinking matters most, another prioritises execution. These disagreements need to be resolved, not papered over. A framework that leadership does not genuinely agree on will not survive contact with calibration.

Start with good examples. You do not need to write descriptions from scratch. Well-crafted examples exist for common competencies across standard role families. Starting with proven templates and customising them to your context is far easier than staring at a blank page. The goal is to capture what your organisation values, not to invent a new vocabulary for universal human capabilities. Clarity Forge can generate starter descriptions based on your roles, levels and chosen competencies — giving you a foundation to refine rather than a blank page to fill.

Ownership and Governance

Who defines competencies? This is a governance question that organisations often ignore until it becomes a problem.

Too centralised: HR defines everything for the entire company. The framework does not fit local reality. Engineering competencies do not make sense for sales. Descriptions are so generic they apply to everyone and therefore help no one.

Too decentralised: Every team defines their own competencies. You are back to inconsistency. A senior engineer in one team is not equivalent to a senior engineer in another. Calibration across teams becomes impossible.

The middle path: Define core competencies at the function or role-family level — all product managers share the same competency framework, all engineers share another. Allow teams to add context or emphasis, but not to override the core. This provides consistency where it matters while leaving room for local reality.

Someone needs to own the framework — to maintain it, facilitate updates and ensure it stays relevant. This is typically HR in partnership with function leaders. But ownership does not mean control. The framework should be shaped by the people who use it, not imposed from above.

Using the Framework

A competency framework is only valuable if it gets used. Here is where it connects to the rest of the clarity system:

Performance conversations. Competencies provide the vocabulary for feedback. Instead of "you need to improve your communication," a manager can say "your written communication is at senior level, but your ability to influence without authority — which is what we expect at principal level — is not there yet. Here is what that looks like..."

Calibration. When managers gather to discuss ratings and promotions, competencies create shared criteria. "We all agree she delivered strong results, but her stakeholder management is still at senior level, not principal" is a conversation that can be resolved. "I think she's ready but you don't" is not.

Development planning. Competencies make growth concrete. An employee preparing an Aspirational Review can identify which competencies they want to demonstrate at the next level. Impact Calibration conversations can focus on how competencies are being perceived.

Promotion cases. When advocating for a promotion, managers can present evidence against each competency. "Here are examples of her operating at principal level in technical judgment, decision making and stakeholder management." This is harder to dismiss than "I think she's ready."

Hiring. Competencies clarify what to evaluate in interviews. Instead of vague assessments of "culture fit," interviewers can assess specific competencies relevant to the role and level.

Signs Articulating Excellence Is Working

- Leaders can articulate what excellence looks like for each role

- Hiring decisions reference competencies, not just skills and experience

- Employees can articulate what is expected of them at their current level

- Employees know what competencies they need to develop to reach the next level

- Managers use competency language in feedback and development conversations

- Calibration discussions reference competency descriptions, not just opinions

- Promotion cases include evidence mapped to competencies

- Different managers evaluating the same employee reach similar conclusions

- The framework gets updated based on feedback from people using it

Signs Articulating Excellence Is Broken

- Leaders complain about the workforce they have but have not defined the workforce they want

- Employees do not know what is expected of them or how to grow

- Competency descriptions exist but no one uses them

- Ratings cluster in the middle because descriptions are too vague to differentiate

- Calibration devolves into "I think" vs "you think" without shared criteria

- Promotions feel arbitrary or political

- Different teams have wildly different standards for the same level

- The framework was created once and never updated

- Leaders cannot agree on what competencies actually matter

Summary

Articulating Excellence transforms vague wishes about your workforce into concrete definitions that can be hired for, developed toward and rewarded.

Every leadership team wants better decision makers, more strategic thinkers, people who take initiative. But until you define what those things look like — at each level, in observable terms — they remain wishes. You cannot hire for competencies you have not defined. You cannot develop people toward standards you have not articulated. You cannot reward behaviours you cannot describe.

The failure to articulate cascades to employees. They do not know how to succeed. Calibration becomes political. Fairness erodes. The same frustrations surface in every town hall.

Competencies are the transferable capabilities that define how good someone is at the craft of their role — decision making, stakeholder management, communication, strategic thinking. The key is defining what each competency looks like at each level. You rate someone as "senior level in decision making" or "principal level in stakeholder management" based on observable descriptions, not abstract numbers.

Writing good descriptions is hard — but you do not have to start from scratch. Good examples exist. The real work is customising them to your context and getting leadership aligned on what actually matters.

When competencies are clear, two things happen. Leaders gain the ability to shape the workforce they want. Employees gain visibility into how to succeed. Both need each other — a vision without visible rules breeds cynicism, and visible rules without vision produce compliance instead of excellence.

Have you defined the workforce you want?

Clarity Forge helps you articulate competencies and generate maturity descriptions — so expectations are visible and excellence is achievable.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.