Exponential Management

People development as a force multiplier.

Purpose

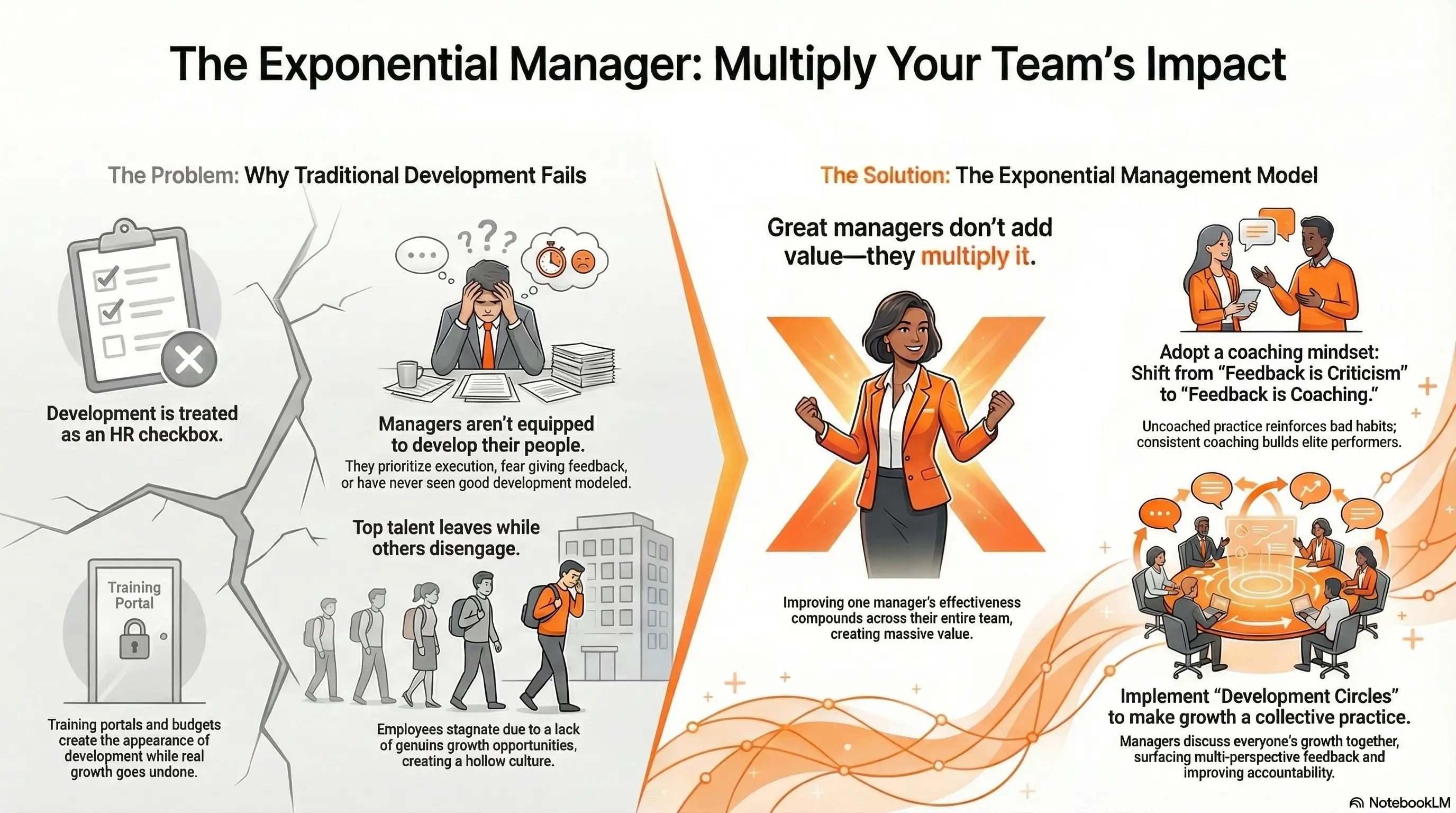

Ask most organisations who is responsible for developing employees and they will point to HR. Ask HR what they do about it and they will describe a training budget - perhaps $100 per employee per year - and a learning portal full of courses no one completes. Maybe an annual development planning template that managers fill out because they have to.

This is not development. It is the appearance of development. A checkbox that lets the organisation say it invests in people while the actual work of growing them goes undone.

The problem is not that HR is failing. It is that HR was never in a position to succeed. Real development does not happen in courses or portals. It happens in the daily interactions between managers and their people — in feedback given, expectations set, challenges assigned, growth recognised. HR cannot do this. Only managers can.

But managers are not doing it either.

Some avoid feedback because they worry it will hurt feelings. "What if it makes them depressed?" a CTO asked me recently. Others believe development is not their job at all. "We expect employees to come to us fully formed," a VP told me. "They are responsible for their own growth." Most simply prioritise execution over talent — there is always a deadline, a crisis, a deliverable that crowds out the development conversation. Talent gets whatever time is left over, which is usually none.

Underneath all of these is a simpler problem: most managers have never seen good development done. They have never had a manager who invested in their growth. They have no model for what it looks like. So they do what they know — they manage tasks, hit deadlines and hope their people figure out the rest.

Meanwhile, employees stagnate. The best ones leave, citing "lack of growth opportunities." The rest disengage, doing the minimum until something better comes along. And organisations wonder why their culture feels hollow despite the training portal and the annual development template.

Exponential Management is a model for changing this. It treats people development as a force multiplier — a craft worth mastering, a collective responsibility and the highest-leverage investment an organisation can make.

The Multiplier Math

A great manager does not add value. They multiply it.

This is not metaphor. Consider: a single contributor's output is bounded by their own capacity — their hours, their skills, their energy. A manager's output is bounded by the capacity of everyone they lead. If a manager makes ten people 20% more effective, they have created two full headcount worth of value. If they make those people 50% more effective, they have created five.

Now extend this. A manager of managers who improves the capability of five managers, each of whom leads ten people, has a leverage ratio of 50:1. A VP or CXO who builds management capability across the organisation operates at leverage ratios that are almost impossible to calculate.

This is the multiplier math. It explains why some organisations dramatically outperform others with similar resources. It is not that they hired better individual contributors. It is that they invested in the layer that multiplies everything else.

Most organisations understand leverage when it comes to technology. They will invest millions in tools that make employees 10% more productive. But they ignore the management layer — the human infrastructure that determines whether people are engaged, growing and doing their best work. They leave that to chance.

The return on improving management quality is higher than almost any other investment. It compounds across every person a manager touches, every year they remain in the role. And unlike technology investments, it does not depreciate.

The Coaching Mindset

Tiger Woods has a coach. He has had one for his entire career. Every day, someone watches his swing, spots flaws he cannot see and helps him improve. He pays handsomely for this — not because he enjoys criticism, but because he knows that uncoached practice just reinforces bad habits. The feedback is not an injury. It is the difference between getting better and staying stuck.

Now consider: do you want an organisation full of Tiger Woods, or an organisation full of people who hit the driving range a few times a year and wonder why they are not improving?

This is the choice most companies make without realising it. They hire talented people, point them at problems and hope for the best. No coaching. No feedback. No one helping them see what they cannot see themselves. Just technically skilled people practising in isolation, reinforcing whatever habits they came in with.

The organisations that outperform are the ones that coach. Not in the formal "executive coaching for senior leaders" sense — though that has value — but in the everyday sense. Managers who watch how their people work, offer observations, help them adjust. Feedback as a regular practice, not an annual event.

This requires a mindset shift:

Old mindset: Feedback is criticism. It damages confidence. Good managers protect their people from it. Employees should arrive fully formed.

New mindset: Feedback is coaching. It builds capability. Good managers provide it consistently because they believe their people can improve. Everyone — no matter how senior — has room to grow.

The question is not whether feedback might be uncomfortable. The question is whether you are building an organisation of coached performers or uncoached ones. The gap between these two widens every year.

The Development Circle

Most organisations treat people development as a private matter between manager and employee. The manager observes, the manager gives feedback, the manager advocates at promotion time. No one else is involved.

This isolation creates problems:

Limited perspective. The direct manager sees one slice of someone's work. They do not see how the person collaborates across teams, how they show up in senior settings, how they handle conflict with peers. They are making development decisions with incomplete information.

Adversarial calibration. When managers only come together to discuss employees at rating time, the dynamic is competitive. I am building a case for my person, which often means undermining yours. Feedback becomes ammunition rather than insight.

No accountability. When development is invisible, managers can neglect it indefinitely. No one knows if they are growing their people or just managing tasks. The manager who avoids hard conversations faces no consequences until their best people leave.

No manager development. Managers figuring it out alone never see how other managers approach the work. They reinvent wheels, repeat mistakes and never develop beyond their starting intuitions.

The Development Circle solves this by making people development a collective practice.

The structure is simple: get all managers in a room — or on a call — and discuss the development of everyone in the organisation, together. Not performance ratings. Not calibration. Development. Where is each person now? Where could they be? What is holding them back? What feedback have they received? What feedback should they receive?

What happens when you do this:

Multi-perspective feedback surfaces. A peer manager mentions that someone struggles with cross-team collaboration. A skip-level notes that they made a strong impression in a recent presentation. Information that would never reach the direct manager suddenly becomes available.

The dynamic flips from adversarial to developmental. When the explicit purpose is growth rather than ratings, managers contribute to each other's people. "I noticed something that might help your engineer" replaces "let me explain why my engineer deserves the higher rating."

Manager accountability becomes visible. When managers discuss development in a group, they cannot hide. If someone is not growing their people, it shows. If someone avoids hard feedback, peers notice.

Managers develop each other. Watching how other managers think about development, hearing how they frame feedback, seeing different approaches — this is professional development for the managers themselves. The Development Circle grows the people who grow the people.

The Loneliness Problem

Who develops the managers?

In most organisations, the answer is no one. Managers are expected to figure out one of the hardest jobs in the organisation with zero support. They get a promotion, perhaps a two-day training course and then they are on their own.

They have no peers to consult when an employee is struggling. No coach to help them navigate a difficult conversation. No structured way to improve at the craft they are now expected to perform. They manage in isolation, making mistakes they cannot see, repeating patterns that do not work.

Then organisations wonder why managers avoid the hard parts. Why they do not give feedback. Why they struggle to develop their people. Why they burn out.

The Development Circle addresses part of this by creating peer learning. But exponential management goes further. It asks: what if we treated manager development with the same seriousness we treat individual contributor development?

This means:

- Manager cohorts — Groups of managers at similar levels who meet regularly to discuss challenges, share approaches and learn from each other

- Manager coaches — Senior leaders or external coaches who work with managers on their craft, not just their business problems

- Manager feedback — 360-degree input on how managers are doing at the job of management, not just the job of delivering results

- Manager progression — Clear expectations for what good management looks like at each level, so managers know what they are developing toward

The lonely manager is a symptom of an organisation that does not take management seriously. Exponential management fixes this by treating the craft as learnable, the practitioners as worthy of investment and the outcomes as too important to leave to chance.

Signs Exponential Management Is Working

- Managers discuss people development in groups, not just bilaterally

- Feedback flows regularly, not just at review time

- Managers can articulate a development path for each of their people

- Employees are rarely surprised by feedback — they have heard it before

- Strong performers are retained because they feel invested in

- Managers learn from each other and visibly improve at the craft

- Calibration conversations focus on contribution and growth, not politics

- The organisation treats management quality as a strategic priority

Signs Exponential Management Is Broken

- "Development" means a training budget and a portal full of unwatched videos

- HR owns the development process; managers see it as someone else's job

- Managers believe employees should "come fully formed" and own their own growth

- Feedback is avoided because it might be uncomfortable — or simply never happens

- Managers figure it out alone with no support or accountability

- Calibration is adversarial — managers advocate for their people by diminishing others

- Strong performers leave citing lack of growth or unclear expectations

- Manager quality varies wildly with no intervention

- Execution always wins; talent development gets whatever time is left over

- "Is that really a manager's role anymore?" is a question people ask sincerely

Summary

Exponential Management treats people development as a force multiplier — the highest-leverage investment an organisation can make.

Most organisations outsource development to HR, who respond with training budgets and learning portals. This is not development. Real development happens in daily interactions between managers and their people. But managers are not doing it — some avoid feedback, some believe employees should arrive fully formed, most simply prioritise execution over talent. And almost none have ever seen good development done.

The multiplier math is simple: managers do not add value, they multiply it. Improving the capability of the management layer compounds across every person they lead. Yet most organisations leave this to chance.

The coaching mindset asks: do you want an organisation of Tiger Woods, or an organisation of people who hit the driving range a few times a year? The gap between coached and uncoached performers widens every year.

The Development Circle makes people growth a collective practice. When managers discuss development together — not just ratings, but growth — multi-perspective feedback surfaces, the adversarial dynamic flips and managers develop each other.

The organisations that win are not the ones with the best individual contributors. They are the ones that invest in the multiplier layer — the managers who grow the people who do the work.

Is your management layer multiplying or just managing?

Clarity Forge makes development visible — so managers grow their people together, not in isolation.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.